Of course! Let's dive deep into synchronized in Java. It's one of the most fundamental and important concepts for writing multi-threaded applications.

What is synchronized?

In simple terms, synchronized is a keyword in Java that is used to provide mutual exclusion and thread safety. It ensures that only one thread can execute a particular block of code or a method on a given object at any given time.

Think of it like a single restroom key in an office. Only the person holding the key (the thread) can use the restroom (the critical code). If the restroom is occupied, others must wait until it's free.

The Core Problem: Race Conditions

To understand why synchronized is needed, let's look at the problem it solves.

Imagine a simple counter:

class Counter {

private int count = 0;

public void increment() {

count++; // This is NOT an atomic operation

}

public int getCount() {

return count;

}

}

In a multi-threaded environment, if two threads call increment() at the same time, what happens?

The count++ statement looks like a single action, but it's actually three separate steps:

- Read: Get the current value of

countfrom memory. - Modify: Add 1 to the value.

- Write: Store the new value back to memory.

Here's how a race condition can occur:

| Thread A | Thread B | What happens to count? |

|---|---|---|

Reads count (value is 10) |

||

Reads count (value is 10) |

Both have the old value. | |

| Adds 1 (value is now 11) | ||

| Adds 1 (value is now 11) | Both have the new value. | |

Writes 11 to count |

||

Writes 11 to count |

The final value is 11. |

Expected Result: 12 Actual Result: 11

This is a race condition. The final result depends on the unpredictable timing of the threads. synchronized fixes this by ensuring that the three steps of count++ are executed as an atomic (indivisible) unit.

How to Use synchronized

There are three primary ways to use the synchronized keyword.

Synchronized Instance Methods

When you declare a method as synchronized, you are locking on the instance of the object (this).

public class MyObject {

public synchronized void instanceMethod() {

// Code here is thread-safe

// Only one thread can execute this method per instance of MyObject at a time.

}

}

How it works:

- Thread A calls

myObject.instanceMethod(). It acquires the lock onmyObject. - While Thread A is inside the method, Thread B calls

myObject.instanceMethod(). It blocks (waits) because the lock onmyObjectis already held by Thread A. - When Thread A finishes the method, it releases the lock. Now, Thread B can acquire the lock and enter the method.

Synchronized Static Methods

When you declare a static method as synchronized, you are locking on the class object (MyClass.class).

public class MyObject {

public static synchronized void staticMethod() {

// Code here is thread-safe

// Only one thread can execute this method for the entire MyObject class at a time.

}

}

How it works:

- There is only one

Classobject for a class in the JVM (e.g.,MyObject.class). - If Thread A calls

MyObject.staticMethod()on any instance, it acquires the lock onMyObject.class. - Thread B calling

MyObject.staticMethod()on any other instance will also block because it's trying to acquire the same class-level lock.

Synchronized Blocks (or Statements)

This is the most flexible way to use synchronization. You can synchronize on a specific object, which is useful when you don't want to lock an entire method.

public class MyObject {

private final Object lock = new Object(); // A dedicated lock object

public void doSomething() {

// Some non-synchronized code

System.out.println("Before synchronized block");

synchronized (this) { // Lock on the current instance

// Critical section - only one thread can execute this per instance

System.out.println("Inside synchronized block on 'this'");

}

synchronized (lock) { // Lock on our dedicated lock object

// Critical section - only one thread can execute this per instance

// This is often preferred over 'this' to avoid external interference

System.out.println("Inside synchronized block on 'lock'");

}

// More non-synchronized code

System.out.println("After synchronized blocks");

}

}

Why use a dedicated lock object?

- Encapsulation: You expose less of your object's internal locking mechanism. If you synchronize on

this, any other code that can access your object can also try to lock on it, leading to potential deadlocks. - Granularity: You can have multiple, independent locks within one object.

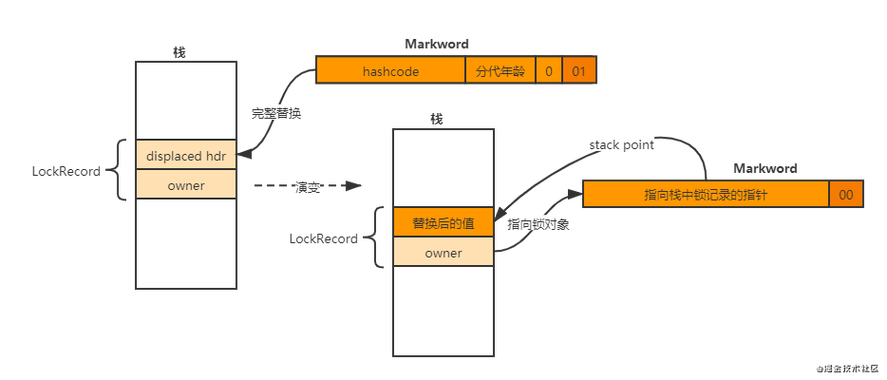

The Lock Mechanism (Intrinsic Lock)

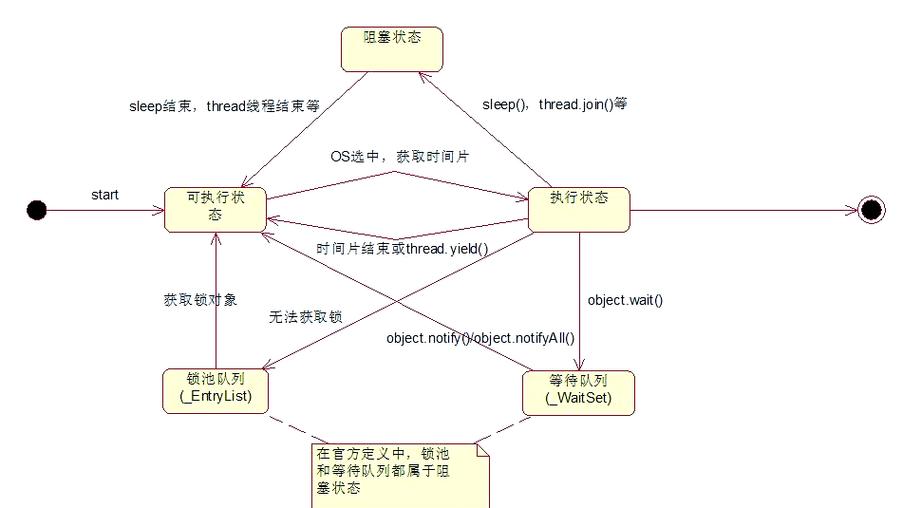

When a thread encounters a synchronized block or method, it tries to acquire an intrinsic lock (also known as a monitor lock) associated with the specified object (this, the class object, or a custom object).

- Rules:

- Only one thread can own the intrinsic lock for an object at a time.

- If a thread tries to enter a

synchronizedblock and the lock is already held, it blocks until the lock is released. - When a thread exits a

synchronizedblock (normally or via an exception), it automatically releases the lock.

Important Considerations and Best Practices

Deadlocks

A deadlock is a situation where two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other to release a lock.

Classic Example:

- Thread 1 locks Lock A and then tries to lock Lock B.

- Thread 2 locks Lock B and then tries to lock Lock A.

- Both threads will wait forever.

// Deadlock Example

final Object lock1 = new Object();

final Object lock2 = new Object();

new Thread(() -> {

synchronized (lock1) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: Holding lock 1...");

try { Thread.sleep(100); } catch (InterruptedException e) {} // Simulate work

System.out.println("Thread 1: Waiting for lock 2...");

synchronized (lock2) { // Deadlock!

System.out.println("Thread 1: Acquired lock 2!");

}

}

}).start();

new Thread(() -> {

synchronized (lock2) {

System.out.println("Thread 2: Holding lock 2...");

try { Thread.sleep(100); } catch (InterruptedException e) {} // Simulate work

System.out.println("Thread 2: Waiting for lock 1...");

synchronized (lock1) { // Deadlock!

System.out.println("Thread 2: Acquired lock 1!");

}

}

}).start();

How to avoid deadlocks:

- Lock Ordering: Always acquire locks in a consistent, global order.

- Lock Timeout: Use

java.util.concurrent.locks.Lockimplementations which supporttryLock()with a timeout. - Avoid Nested Locks: Keep synchronized blocks short and avoid calling unknown code from within them.

Performance Overhead

Synchronization has a performance cost due to the overhead of acquiring and releasing locks, and context switching when threads are blocked. Don't use it unnecessarily.

Liveness vs. Safety

- Safety: Ensuring that nothing bad ever happens (e.g., no race conditions, data corruption).

synchronizedprovides safety. - Liveness: Ensuring that something good eventually happens (e.g., the program doesn't deadlock or starve).

synchronizedcan harm liveness if not used carefully (e.g., causing deadlocks).

synchronized vs. java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock

| Feature | synchronized |

java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock |

|---|---|---|

| How it's acquired | Automatically when entering a block/method. | Explicitly via lock.lock(). |

| How it's released | Automatically when exiting a block/method (even via exception). | Explicitly via lock.unlock(). Must be in a finally block! |

| Interruptible | No. A blocked thread cannot be interrupted. | Yes. lock.lockInterruptibly() allows a thread to be interrupted while waiting. |

| Fairness | Unfair (non-reentrant, but can be reentrant). Can lead to thread starvation. | Can be fair (by passing true to constructor) or unfair. Fairness reduces starvation but is slower. |

| Condition Variables | No. | Yes. A Lock can have one or more Condition objects for more sophisticated thread signaling. |

Modern Recommendation:

- For most simple cases,

synchronizedis perfectly fine and often preferred for its simplicity. - For advanced scenarios like try-lock, timed locks, interruptible locks, or fairness, use the

java.util.concurrent.lockspackage.

Modern Alternatives

Since Java 5, the java.util.concurrent package provides higher-level abstractions that are often better and safer than using synchronized directly.

-

java.util.concurrent.atomicclasses: For simple atomic operations (like ourcount++example). These classes use highly optimized, low-level hardware instructions (likecompare-and-swap) and avoid the overhead of traditional locks.import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger; class Counter { private final AtomicInteger count = new AtomicInteger(0); public void increment() { count.getAndIncrement(); // This is atomic and lock-free } } -

java.util.concurrentcollections: Classes likeConcurrentHashMap,CopyOnWriteArrayList, etc., are designed for concurrent access and manage their own synchronization internally, often more efficiently than a simplesynchronizedwrapper.

Summary

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To ensure thread safety by preventing race conditions. |

| Mechanism | Uses intrinsic locks (monitors) on objects. |

| Usage | synchronized methods or blocks. |

| Key Rule | Only one thread can hold the lock for a given object at a time. |

| Pros | Simple, easy to use, built into the language. Guarantees atomicity, visibility, and ordering. |

| Cons | Can lead to deadlocks. Can have performance overhead. Less flexible than java.util.concurrent.locks. |

| Best Practice | Keep synchronized blocks as short as possible. Use dedicated lock objects instead of this. Consider java.util.concurrent alternatives for complex scenarios. |