Of course! Let's break down synchronized in Java in a comprehensive way, from the basic concept to practical examples and best practices.

What is the Problem? Why Do We Need synchronized?

Imagine a bank account with two threads: one for deposits and one for withdrawals. Without any protection, this could happen:

- Thread A (Withdrawal): Reads the balance, say

$100. - Thread B (Deposit): Reads the balance, also

$100, and deposits$50. The balance is now$150. Thread B writes the new balance back. - Thread A (Withdrawal): Continues its operation. It has the original balance (

$100) and subtracts$20. It calculates the new balance as$80and writes it back.

The Result: The balance is $80, but it should be $130 ($150 - $20). This is a classic race condition, where the final result depends on the unpredictable timing of thread execution.

synchronized is Java's built-in mechanism to prevent these race conditions by ensuring that only one thread can execute a specific block of code or method at a time.

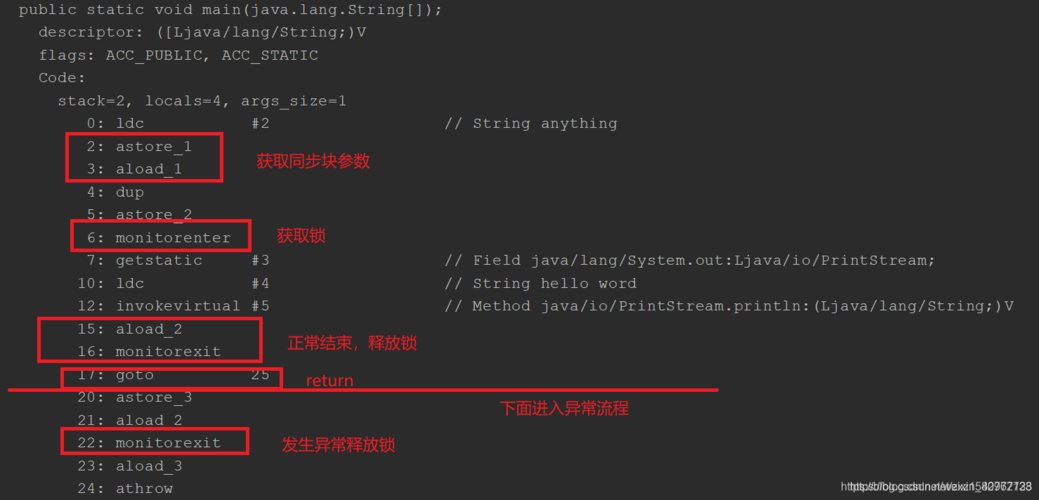

The Core Concept: The Lock

At its heart, synchronized is all about locks. Every object in Java has an intrinsic lock (also called a monitor lock).

- When a thread encounters a

synchronizedblock or method, it must first acquire the lock associated with the object specified. - If the lock is available, the thread acquires it, executes the code, and then releases the lock when it's done (or if an exception occurs).

- If another thread tries to enter the same

synchronizedblock while the lock is held, it is blocked (waits) until the lock is released.

This mutual exclusion ensures that only one thread can be inside the synchronized section for a given lock at any moment, effectively preventing race conditions.

How to Use synchronized

There are three primary ways to use the synchronized keyword.

A. Synchronized Instance Methods

When you declare an instance method as synchronized, the lock is the instance itself (i.e., this).

public class Counter {

private int count = 0;

// The lock is the 'this' object (the instance of Counter)

public synchronized void increment() {

count++;

}

public synchronized int getCount() {

return count;

}

}

How it works:

- If

thread1callscounter.increment(), it acquires the lock on thecounterobject. - Any other thread that tries to call

counter.increment()orcounter.getCount()on the samecounterobject will be blocked untilthread1releases the lock.

B. Synchronized Static Methods

When you declare a static method as synchronized, the lock is the Class object associated with the class. This means the lock is shared across all instances of the class.

public class SharedResource {

// The lock is the SharedResource.class object

public static synchronized void doSomething() {

// ... critical section ...

}

}

How it works:

- If

thread1callsSharedResource.doSomething()from one part of the application, it acquires the lock on theSharedResource.classobject. - Any other thread, anywhere in the application, that tries to call

SharedResource.doSomething()will be blocked, regardless of which instance ofSharedResource(or even if there are no instances) it's being called from.

C. Synchronized Blocks (Most Flexible)

This is often the preferred method because it allows you to synchronize on a specific object, reducing the scope of the lock and potentially increasing concurrency.

The syntax is: synchronized (lockObject) { /* critical section */ }

public class BankAccount {

private double balance;

private final Object lock = new Object(); // A dedicated lock object

public void deposit(double amount) {

// We only need to lock the transfer logic, not the whole method

synchronized (lock) { // The lock is our 'lock' object

balance += amount;

}

// Other threads can execute non-synchronized code here concurrently

}

public void withdraw(double amount) {

synchronized (lock) { // The same lock object is used

if (balance >= amount) {

balance -= amount;

}

}

}

}

Why use a dedicated lock object?

- Finer-grained control: You can protect only the specific code that needs it, rather than the entire method.

- Avoiding external interference: If you synchronize on

this, external code could also acquire the lock on your object, potentially causing deadlocks. Aprivate finallock object is encapsulated and safe. - Separate locks: You can have multiple locks for different parts of an object. For example, you could have one lock for the balance and another for a list of transactions, allowing those operations to happen in parallel as long as they don't touch the same resource.

A Complete, Practical Example

Let's model our bank account scenario.

public class BankAccount {

private double balance = 100.0;

// Use a dedicated lock object for clarity and safety

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void deposit(double amount) {

synchronized (lock) {

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " is depositing " + amount);

double newBalance = balance + amount;

// Simulate some processing time

try { Thread.sleep(10); } catch (InterruptedException e) {}

balance = newBalance;

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " deposited. New balance: " + balance);

}

}

public void withdraw(double amount) {

synchronized (lock) {

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " is withdrawing " + amount);

if (balance >= amount) {

double newBalance = balance - amount;

// Simulate some processing time

try { Thread.sleep(10); } catch (InterruptedException e) {}

balance = newBalance;

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " withdrew. New balance: " + balance);

} else {

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " failed to withdraw. Insufficient funds. Balance: " + balance);

}

}

}

public double getBalance() {

return balance;

}

}

// Main class to run the simulation

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

BankAccount account = new BankAccount();

// Thread 1: Depositor

Thread depositorThread = new Thread(() -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

account.deposit(10.0);

}

}, "Depositor");

// Thread 2: Withdrawer

Thread withdrawerThread = new Thread(() -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

account.withdraw(15.0);

}

}, "Withdrawer");

depositorThread.start();

withdrawerThread.start();

try {

depositorThread.join();

withdrawerThread.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("\nFinal Balance: " + account.getBalance());

}

}

Expected Output (order of lines may vary, but the final balance will be consistent):

Depositor is depositing 10.0

Depositor deposited. New balance: 110.0

Withdrawer is withdrawing 15.0

Withdrawer withdrew. New balance: 95.0

Depositor is depositing 10.0

Depositor deposited. New balance: 105.0

Withdrawer is withdrawing 15.0

Withdrawer withdrew. New balance: 90.0

... (and so on) ...

Final Balance: 75.0Notice how the deposit and withdraw operations on the same account never overlap. The synchronized (lock) block ensures they are executed atomically.

Important Considerations and Best Practices

Deadlocks

A deadlock occurs when two or more threads are blocked forever, each waiting for the other to release a lock.

Classic Example:

- Thread 1 locks Lock A and waits for Lock B.

- Thread 2 locks Lock B and waits for Lock A.

How to avoid:

- Lock Ordering: Always acquire locks in a consistent, global order. (e.g., always acquire Lock A before Lock B).

- TryLock: Use

java.util.concurrent.locks.Lockinterface and itstryLock()method, which attempts to acquire the lock but doesn't block forever. - Avoid Nested Locks: Be very careful when a synchronized method calls another synchronized method on the same object.

Performance Overhead

Synchronization has a cost. Acquiring and releasing locks takes time. If you over-synchronize, you can hurt performance by making your program more sequential.

Solution: Synchronize only the critical section—the smallest piece of code that absolutely must be atomic. Using synchronized blocks is better for this than synchronized methods.

Reentrancy

Java's locks are reentrant. This means a thread can reacquire a lock it already holds. This is essential for recursive methods.

public class ReentrantExample {

public synchronized void doSomething() {

System.out.println("Lock held by " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

// A thread can call another synchronized method on the same object

doSomethingElse();

}

public synchronized void doSomethingElse() {

// This can enter because the thread already holds the lock

System.out.println("Inside reentrant method.");

}

}

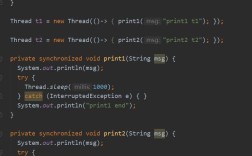

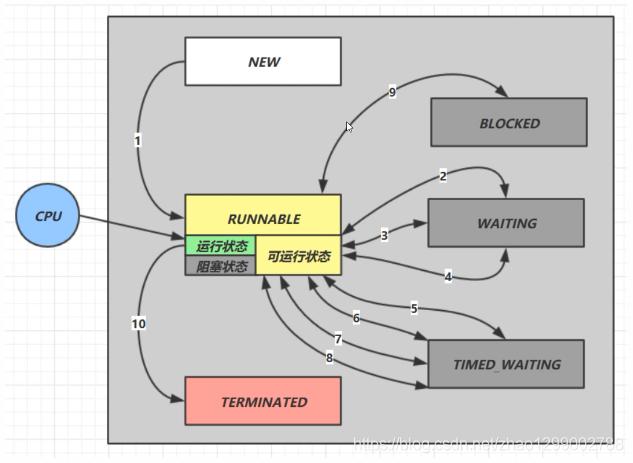

wait(), notify(), and notifyAll()

Inside a synchronized block, you can use these methods from the Object class for more advanced thread communication:

wait(): Causes the current thread to release the lock and wait until another thread callsnotify()ornotifyAll().notify(): Wakes up a single thread that is waiting on this object's lock.notifyAll(): Wakes up all threads that are waiting on this object's lock.

This is the foundation of the Producer-Consumer pattern.

Modern Alternatives (The java.util.concurrent Package)

For most new code, it's better to use the high-level concurrency utilities from java.util.concurrent instead of raw synchronized blocks. They are more powerful, flexible, and less error-prone.

ReentrantLock: A more powerful version of the intrinsic lock. It offers features liketryLock(), fairness policies, and multipleConditionobjects (a replacement forwait/notify).Atomicclasses (e.g.,AtomicInteger,AtomicReference): These classes use low-level hardware instructions (like Compare-And-Swap) to provide lock-free, thread-safe operations on single variables. They are extremely fast for simple operations like incrementing a counter.BlockingQueue: The perfect tool for the Producer-Consumer pattern, handling all the synchronization and waiting for you.

Summary

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To prevent race conditions and ensure thread safety by allowing only one thread to execute a block of code at a time. |

| Mechanism | Relies on intrinsic locks (or monitors) associated with every object. |

| Forms | Synchronized Method: Lock is this (instance) or ClassName.class (static). 2. Synchronized Block: Lock is any specified object. More flexible. |

| Key Concept | Mutual Exclusion: Only one thread can hold the lock at a time. |

| Pros | Simple to use, built into the language, reentrant. |

| Cons | Can lead to deadlocks, can hurt performance if overused, less flexible than modern alternatives. |

| Best Practice | Synchronize the smallest possible critical section. Prefer synchronized blocks over methods. For new code, consider java.util.concurrent utilities like ReentrantLock and AtomicInteger. |