Of course! Let's dive deep into Python annotations, starting from the basics and moving to more advanced and practical use cases.

What are Python Annotations?

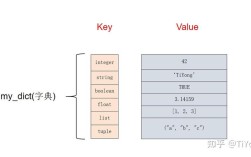

In short, Python annotations are a way to add type information to your code. They are a form of metadata that you can attach to variables, function parameters, and function return values.

Key Point: Annotations are optional and are primarily used for static type checking. They do not affect the runtime behavior of your Python code (unless you explicitly use them to do so).

Think of them as a form of documentation for both other developers and for automated tools.

The Syntax: How to Write Annotations

The syntax uses a colon () for variables and parameters, and an arrow (->) for return values.

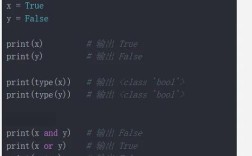

A. Variable Annotations

You can declare the type of a variable directly.

# Before annotations (no type info) name = "Alice" age = 30 is_student = True # With annotations (type is now explicit) name: str = "Alice" age: int = 30 is_student: bool = True # You can also annotate a variable without assigning a value pi: float # print(pi) # This would raise a NameError, as it's not defined yet pi = 3.14159

B. Function and Method Annotations

This is where annotations are most commonly used.

- Parameter Annotations: After the parameter name, followed by a colon.

- Return Annotation: After the parameter list, followed by

->and the type.

def greet(name: str) -> str:

"""Greets a person by name and returns a greeting string."""

return f"Hello, {name}!"

def calculate_area(width: float, height: float) -> float:

"""Calculates the area of a rectangle."""

return width * height

def get_user_data(user_id: int, is_active: bool = True) -> dict:

"""

Simulates fetching user data.

The default value for is_active is True.

"""

# This is just a simulation

return {"id": user_id, "is_active": is_active}

C. Complex Types

Annotations can become much more complex to accurately describe your data structures.

from typing import List, Dict, Tuple, Optional, Union

# A list of integers

scores: List[int] = [98, 87, 91]

# A dictionary mapping strings to integers

inventory: Dict[str, int] = {"apples": 50, "oranges": 30}

# A tuple with specific types for each position

point: Tuple[int, int, int] = (10, 20, 30)

# A value that can be either a string or None

middle_name: Optional[str] = None # Same as Union[str, None]

# A value that can be an integer OR a string

identifier: Union[int, str] = 123

identifier = "ABC-123"

# A list of dictionaries, where each dict has string keys and float values

product_data: List[Dict[str, float]] = [

{"price": 19.99, "weight": 1.5},

{"price": 5.49, "weight": 0.2}

]

Why Use Annotations? (The Benefits)

-

Static Type Checking: This is the #1 reason. Tools like Mypy, Pyright, and Pyre can read your source code (without even running it) to find type errors.

(图片来源网络,侵删)

(图片来源网络,侵删)- Example: If you write a function that expects an

intbut you accidentally pass astr, a type checker will flag this as an error before it ever causes a bug in production.

- Example: If you write a function that expects an

-

Improved IDE Support: Modern IDEs like VS Code and PyCharm use annotations to provide incredible features:

- Autocompletion: They can suggest methods that are valid for a specific type.

- Error Highlighting: They can spot type mismatches directly in your editor as you type.

- Go-to-Definition: They can accurately navigate to the definition of a variable or function based on its type.

- Hover Information: Hovering over a variable can show you its expected type.

-

Self-Documenting Code: Annotations act as inline documentation. When you read a function signature like

process_data(data: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> bool, you immediately know what kind of data it expects and what it returns, without even reading the docstring. -

Enforcing API Contracts: In large projects, annotations help ensure that different parts of your code (modules, classes, functions) interact with each other in a predictable way. They define a "contract" for the data being passed around.

The typing Module: Your Toolbox for Advanced Types

For anything beyond basic types, you'll need the typing module, which was introduced in Python 3.5. It provides a rich set of special types to handle complex scenarios.

| Type / Construct | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Any |

A special type that means "anything goes". Bypasses type checking. | data: Any = "some value" |

Union[Type1, Type2] |

A value that can be one of several types. Optional[T] is Union[T, None]. |

id: Union[int, str] |

List[T] |

A list where all elements are of type T. |

items: List[str] |

Dict[K, V] |

A dictionary with keys of type K and values of type V. |

config: Dict[str, int] |

Tuple[T1, T2, ...] |

A tuple with a fixed number of items and specific types for each. | point: Tuple[float, float] |

Optional[T] |

A value that can be T or None. Shorthand for Union[T, None]. |

middle_name: Optional[str] |

Callable[[Arg1, Arg2], ReturnType] |

A function or other callable object. | callback: Callable[[str, int], bool] |

TypeVar |

A generic type variable, used to create generic functions or classes. | T = TypeVar('T') |

Generic[T] |

Used to create generic base classes. | class Box(Generic[T]): ... |

Note: Since Python 3.9, you can often use built-in types like list, dict, and tuple directly instead of List, Dict, and Tuple from the typing module. This is called PEP 585.

# Python 3.5 - 3.8 (Old way)

from typing import List, Dict

names: List[str] = ["Alice", "Bob"]

scores: Dict[str, int] = {"Alice": 95, "Bob": 88}

# Python 3.9+ (New way - preferred)

names: list[str] = ["Alice", "Bob"]

scores: dict[str, int] = {"Alice": 95, "Bob": 88}

Runtime vs. Compile Time: A Crucial Distinction

This is a very important concept for Python developers.

Annotations are stored as strings in a special attribute of the function or module. They are not evaluated at runtime.

def add(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

# Let's inspect the function object

print(add.__annotations__)

# Output: {'a': <class 'int'>, 'b': <class 'int'>, 'return': <class 'int'>}

# You can even access them programmatically

param_type = add.__annotations__['a']

print(param_type) # Output: <class 'int'>

# This means you CAN still pass the wrong type, and it will run (but might fail later)

result = add("hello", "world") # This is allowed by Python at runtime

print(result) # Output: helloworld

Because of this, annotations do not prevent runtime errors. Their power is unlocked by external tools.

Practical Example: Running a Type Checker

Let's see how Mypy, the most popular static type checker, works.

Step 1: Install Mypy

pip install mypy

Step 2: Write a Python file with a type error (example.py)

from typing import List

def process_items(items: List[str]) -> int:

"""Counts the total length of all strings in the list."""

total_length = 0

for item in items:

# The developer intended to get the length, but made a mistake.

total_length += item # This should be item.length or len(item)

return total_length

# This call is also problematic

result = process_items(123) # Should be a list of strings, not an int

print(f"The result is: {result}")

Step 3: Run the Python file It will run without crashing, but the output is wrong and the logic is flawed.

python example.py # Output: The result is: 123 (because it's just adding the number 123 to 0)

Step 4: Run Mypy on the file Mypy analyzes the code without running it and finds the type errors.

mypy example.py

Output from Mypy:

example.py:10: error: Argument 1 to "process_items" has incompatible type "int"; expected "List[str]" [arg-type]

example.py:6: error: Unsupported operand types for += ("str" and "int") [operator]

Found 2 errors in 1 file (checked 1 source file)Mypy caught both errors: the wrong argument type and the type mismatch inside the function loop, helping you fix the bug before you even ran the code.

Modern Developments: from __future__ import annotations

In Python 3.7+, you can add from __future__ import annotations to the top of your file. This changes how annotations are handled: they are stored as strings and are never evaluated at import time.

Why is this useful? It solves a problem where a type annotation might refer to a class that hasn't been defined yet.

Without from __future__ import annotations:

# This will raise a NameError

class User:

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

def get_profile(self) -> Profile: # Profile is not defined yet!

return Profile(self.name)

class Profile:

def __init__(self, user_name: str):

self.user_name = user_name

This fails because Profile is not in scope when User.get_profile is defined.

With from __future__ import annotations:

from __future__ import annotations # Must be the VERY first line!

class User:

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

def get_profile(self) -> Profile: # This now works!

return Profile(self.name)

class Profile:

def __init__(self, user_name: str):

self.user_name = user_name

By using the future import, "Profile" is just a string literal, so Python doesn't try to resolve it until the type checker (or some other tool) looks at it. This is the modern, recommended way to write type hints in complex class definitions.

Summary

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| What | Optional metadata for adding type hints to code. |

| Syntax | variable: type, func(param: type) -> return_type |

| Purpose | Static type checking, IDE support, and self-documentation. |

| Runtime | Do not affect runtime behavior; are stored as strings. |

| Key Tool | The typing module for advanced types (since Python 3.5). |

| Modern Way | Use built-in list, dict, etc. (Python 3.9+) and from __future__ import annotations. |

| Checker | Use tools like Mypy to find errors based on annotations. |