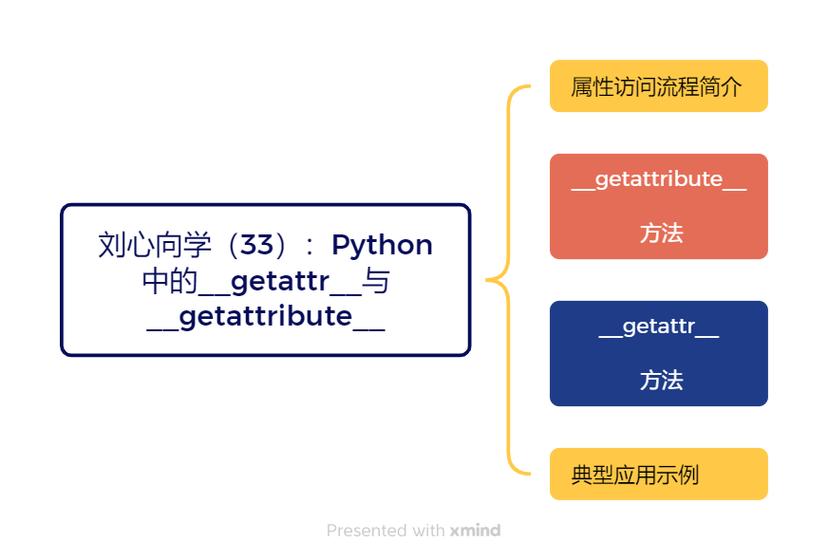

Of course! Let's dive deep into Python's __getattribute__ method. This is a powerful but advanced feature that gives you fine-grained control over attribute access.

The Big Picture: How Attribute Lookup Works in Python

When you access an attribute on an object (e.g., my_obj.some_attr or my_obj.method()), Python doesn't just magically find it. It follows a specific, well-defined order, known as the Attribute Resolution Order. Think of it as a set of rules Python follows to find the attribute.

Here is a simplified version of the lookup order:

__getattribute__: This is the first stop. It's called unconditionally for every attribute access. If you define this method, it's your first chance to intercept the request.- Data Descriptors: If the attribute isn't found in

__getattribute__(or if__getattribute__is not defined), Python looks for the attribute's name in the object's class dictionary. If it finds a data descriptor (an object with both__get__and__set__methods), it calls the descriptor's__get__method. - Instance Dictionary (

__dict__): If no data descriptor is found, Python looks directly in the instance's own dictionary (instance.__dict__). - Class Dictionary: If not found in the instance, Python looks in the class's dictionary.

- Parent Class Dictionaries: If not found in the class, Python continues up the inheritance hierarchy.

- Non-Data Descriptors: If the attribute is found in a parent class but is a non-data descriptor (an object with only

__get__), its__get__method is called. __getattr__: If the attribute has still not been found anywhere, Python checks if the class has a__getattr__method. If it does, this method is called with the missing attribute name as an argument. This is your last-chance fallback.AttributeError: If__getattr__is not defined or it raises anAttributeErroritself, Python gives up and raises anAttributeError.

__getattribute__: The Universal Interceptor

__getattribute__ is a special method that you can define in your class to override the default behavior for every single attribute access.

The Signature

def __getattribute__(self, name):

# Your custom logic here

# ...

# You MUST return the attribute's value or call the super() method

self: The instance of the class.name: A string containing the name of the attribute being accessed (e.g.,'x','method').

The Golden Rule of __getattribute__

Because __getattribute__ is called for every attribute access, including the access to __dict__ itself, you must be very careful. If you try to access any attribute inside __getattribute__ without using super(), you will cause a recursive loop and a RecursionError.

The Wrong Way (Causes Recursion):

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __getattribute__(self, name):

# This will cause a RecursionError!

# Because accessing 'self.value' calls __getattribute__ again.

# And accessing 'self.__dict__' also calls __getattribute__!

if name == 'value':

return "You can't see the real value!"

return self.__dict__[name] # Recursion!

The Right Way (Using super()):

The correct way to get an attribute's value from within __getattribute__ is to delegate the call to the parent class's implementation using super().

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __getattribute__(self, name):

print(f"__getattribute__ called for attribute: '{name}'")

# Delegate to the parent class to avoid recursion

attribute_value = super().__getattribute__(name)

# Now you can inspect or modify the value before returning it

if name == 'value':

print(f" -> Intercepted 'value'. Original value: {attribute_value}")

return f"Intercepted: {attribute_value}"

return attribute_value

Let's test it:

obj = MyClass(42)

print(obj.value)

# Output:

# __getattribute__ called for attribute: 'value'

# -> Intercepted 'value'. Original value: 42

# Intercepted: 42

print(obj.__dict__)

# Output:

# __getattribute__ called for attribute: '__dict__'

# {'value': 42}

Notice that even accessing __dict__ goes through our __getattribute__ method!

Practical Use Cases for __getattribute__

While powerful, __getattribute__ can be overkill. It's best used for debugging, logging, or implementing complex proxy-like objects.

Use Case 1: Logging All Attribute Access

This is a classic example for debugging or understanding how an object is being used.

class LoggedObject:

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

# Use super() to set initial attributes to avoid recursion

for key, value in kwargs.items():

super().__setattr__(key, value)

def __getattribute__(self, name):

print(f"ACCESSING: {name}")

# Delegate to the parent to get the actual value

return super().__getattribute__(name)

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

print(f"SETTING: {name} = {value}")

# Delegate to the parent to set the actual value

super().__setattr__(name, value)

# --- Test ---

user = LoggedObject(name="Alice", age=30)

print("\n--- Accessing attributes ---")

print(f"Name: {user.name}")

print(f"Age: {user.age}")

print("\n--- Modifying an attribute ---")

user.age = 31

print(f"New Age: {user.age}")

Output:

SETTING: name = Alice

SETTING: age = 30

--- Accessing attributes ---

ACCESSING: name

Name: Alice

ACCESSING: age

Age: 30

--- Modifying an attribute ---

SETTING: age = 31

ACCESSING: age

New Age: 31Note: We also needed to override __setattr__ for consistency, as it's called when you assign to an attribute like user.age = 31.

Use Case 2: Creating a "Smart" Proxy or Lazy Loader

Imagine you have a class that's expensive to initialize. You can use __getattribute__ to defer the initialization until an attribute is actually needed.

class ExpensiveObject:

def __init__(self):

print("ExpensiveObject is being initialized...")

self.data = [i**2 for i in range(1000)] # Expensive operation

def process(self):

return sum(self.data)

class LazyProxy:

def __init__(self):

self._real_object = None # The expensive object is not created yet

def __getattribute__(self, name):

# If we are trying to access the internal _real_object, handle it directly

if name == '_real_object':

return super().__getattribute__(name)

# If the real object hasn't been created, create it now

real_object = super().__getattribute__('_real_object')

if real_object is None:

print("Proxy is now creating the ExpensiveObject on demand...")

super().__setattr__('_real_object', ExpensiveObject())

real_object = super().__getattribute__('_real_object')

# Delegate the attribute access to the newly created real object

return getattr(real_object, name)

# --- Test ---

print("Creating the proxy...")

lazy_proxy = LazyProxy()

print("Proxy created. The expensive object has NOT been initialized yet.")

print("\n--- Accessing an attribute for the first time ---")

# This is when the expensive object gets created

result = lazy_proxy.process()

print(f"Result from process(): {result}")

print("\n--- Accessing the same attribute again ---")

# This time, the object already exists, so no initialization happens

result2 = lazy_proxy.process()

print(f"Result from process(): {result2}")

Output:

Creating the proxy...

Proxy created. The expensive object has NOT been initialized yet.

--- Accessing an attribute for the first time ---

Proxy is now creating the ExpensiveObject on demand...

ExpensiveObject is being initialized...

Result from process(): 331667

--- Accessing the same attribute again ---

Result from process(): 331667__getattribute__ vs. __getattr__

This is a common point of confusion. Let's clarify the difference.

| Feature | __getattribute__(self, name) |

__getattr__(self, name) |

|---|---|---|

| When is it called? | Always. On every attribute access. | Only as a fallback. Only if the attribute was not found by the normal lookup process. |

| Purpose | To override the default attribute lookup mechanism entirely. | To handle missing attributes gracefully. |

| Recursive Risk | High. You must use super() to get attributes or you'll get a RecursionError. |

None. By the time it's called, the normal lookup has already failed, so you can safely access attributes. |

| Typical Use Case | Debugging, logging, creating proxies, intercepting all access. | Providing default values, computing attributes on the fly, implementing duck typing. |

Example of __getattr__:

class User:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def __getattr__(self, name):

# This is only called if 'name' is not found on the instance or class

if name == 'full_name':

return f"Mr. {self.name}"

raise AttributeError(f"'{self.__class__.__name__}' object has no attribute '{name}'")

user = User("Bob")

print(user.name) # Accesses 'name' normally. __getattr__ is NOT called.

print(user.full_name) # 'full_name' doesn't exist, so __getattr__ is called.

# Output: Mr. Bob

print(user.email) # 'email' doesn't exist and __getattr__ doesn't handle it.

# Output: AttributeError: 'User' object has no attribute 'email'

Summary

- Use

__getattribute__when you need to intercept every single attribute access for logging, debugging, or creating complex proxy objects. - It is powerful but dangerous due to the risk of infinite recursion if you don't use

super()to access attributes within it. - For most cases where you just want to handle missing attributes, use

__getattr__. It's safer, more intuitive, and doesn't interfere with normal attribute access. - Remember the Attribute Resolution Order:

__getattribute__-> Descriptors ->__dict__-> Inheritance ->__getattr__.