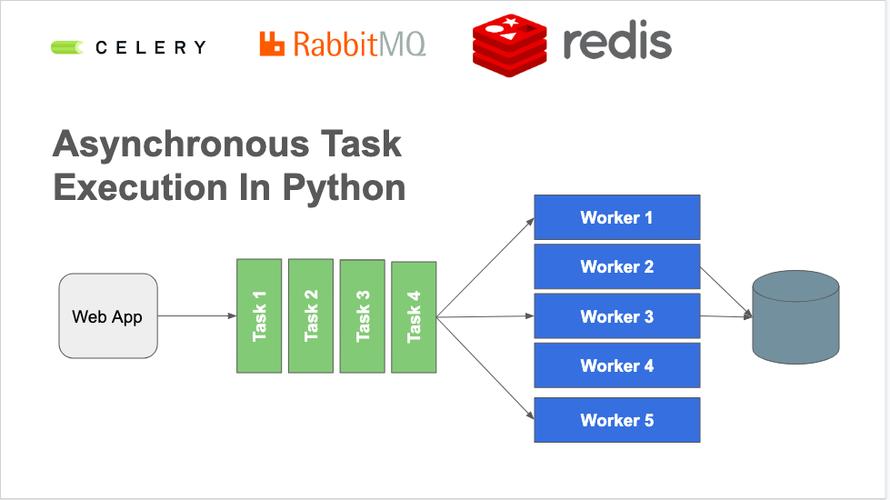

Of course! Here is a comprehensive guide to celeryconfig.py in Python, covering its purpose, common settings, best practices, and modern alternatives.

What is celeryconfig.py?

celeryconfig.py is a Python file used to configure your Celery application. It's a simple and straightforward way to centralize all your Celery-related settings, such as the message broker URL, result backend, task serialization format, and worker behavior.

While Celery is flexible and allows you to configure settings in many ways, celeryconfig.py was the traditional and most common method for a long time.

The Basic Structure

A typical celeryconfig.py file contains a dictionary named CELERY_CONFIG (or simply CELERY). You then import this dictionary into your main Celery application file.

celeryconfig.py

# celeryconfig.py

# Broker settings

# Use RabbitMQ as the message broker

broker_url = 'amqp://guest@localhost:5672//'

# Backend settings

# Store task results in Redis

result_backend = 'redis://localhost:6379/0'

# Task serialization format

# Use JSON for task arguments and results

task_serializer = 'json'

result_serializer = 'json'

accept_content = ['json']

# Time limits for tasks

# A soft time limit of 10 seconds and a hard time limit of 60 seconds

task_soft_time_limit = 10

task_time_limit = 60

# Time to keep results in the backend

# Results are stored for 1 hour

result_expires = 3600

# List of modules to import when the worker starts

# This ensures your tasks are registered with the Celery app

imports = ('myapp.tasks',)

myapp/celery.py (The main app file)

# myapp/celery.py

from celery import Celery

# Create the Celery application instance

app = Celery('myapp')

# Load the configuration from celeryconfig.py

# The 'celeryconfig' module must be in your Python path

app.config_from_object('celeryconfig', force=True)

# Optional: Auto-discover tasks in a 'tasks.py' file in all modules

# in the 'myapp' directory.

app.autodiscover_tasks()

myapp/tasks.py (Where your tasks live)

# myapp/tasks.py

from .celery import app

@app.task

def add(x, y):

"""A simple task that adds two numbers."""

print(f"Adding {x} + {y}")

return x + y

@app.task(bind=True)

def long_running_task(self):

"""A task that reports its progress."""

import time

for i in range(10):

time.sleep(1)

self.update_state(state='PROGRESS', meta={'current': i, 'total': 10})

return {'result': 10}

Common Settings Explained

Here is a breakdown of the most important settings you'll find in celeryconfig.py.

| Setting | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

broker_url |

Required. The URL of the message broker. Celery uses this to send and receive messages (tasks). | amqp://user:password@hostname:port/virtual_hostredis://localhost:6379/0 |

result_backend |

Recommended. The URL of the backend where task results are stored. If not set, results are discarded. | rpc:// (RabbitMQ RPC)redis://localhost:6379/0db+sqlite:///results.db |

task_serializer |

The serializer used for task arguments. json is the most common and secure choice. pickle is also available but can be a security risk if you don't trust the source of the messages. |

'json' |

result_serializer |

The serializer used for task results. | 'json' |

accept_content |

A list of content types (serializers) that the worker will accept. This is a security measure to prevent workers from executing tasks with untrusted serializers. | ['json'] |

timezone |

The timezone used for all times and dates in Celery. It's best practice to set this to UTC. | 'UTC' |

enable_utc |

If True, all times will be in UTC. Should be True if timezone is set. |

True |

task_routes |

A dictionary or list of routes to direct tasks to specific queues. This is essential for task prioritization and isolation. | { 'myapp.tasks.add': {'queue': 'math_queue'}, 'myapp.tasks.email.send': {'queue': 'email_queue'} } |

task_queues |

Defines the queues your application uses. This allows you to configure queue-specific settings like exchange and routing_key. |

{'math_queue': {'exchange': 'math', 'routing_key': 'math'}} |

task_default_queue |

The default queue for tasks that don't have an explicit route. | 'default' |

task_default_exchange |

The default exchange for tasks. | 'default' |

task_default_routing_key |

The default routing key for tasks. | 'default' |

task_soft_time_limit |

The "soft" time limit. If a task exceeds this, a SoftTimeLimitExceeded exception is raised, but the task is not killed. |

300 (5 minutes) |

task_time_limit |

The "hard" time limit. If a task exceeds this, it is terminated by a signal. | 600 (10 minutes) |

result_expires |

How long, in seconds, to keep the result of a task in the backend. After this time, the result is deleted. | 3600 (1 hour) |

imports |

A list of Python modules to import when the worker starts. This is how Celery discovers your tasks. | ('myapp.tasks', 'myapp.other_tasks') |

How to Run Celery with the Config File

Once your celeryconfig.py and main app file are set up, you can start the Celery worker from your terminal.

- Make sure your virtual environment is active.

- Navigate to the directory containing

myappandceleryconfig.py. - Run the

celerycommand, pointing it to your app module.

# The format is: celery -A <app_name>.celery worker --loglevel=info # For our example: celery -A myapp.celery worker --loglevel=info

You should see output like this, confirming the worker has started and loaded the configuration:

-------------- celery@my-machine v5.3.1 (dawn-chorus)

--- * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

-- * _____ __ _ _ *

-- * | __ \ / _|(_) | | *

-- * | |__) | __ ___ ___| |_ _ ___ __ _| |_ ___ _ __ __ _ *

-- * | ___/ '__/ _ \ / _ \ _|| |/ __/ _` | __/ _ \| '_ \ / _` | *

-- * | | | | | (_) | __/ | | | | | (_| | || (_) | | | | (_| | *

-- * |_| |_| \___/ \___|_| |_|_|_|\__,_|\__\___/|_| |_|\__, | *

-- * __/ | *

-- * |___/ *

-- **** -----

- ** * Linux-5.15.0-76-generic-x86_64-with-glibc2.31 2025-10-27 10:30:00

- ** .> app: myapp

- ** .> transport: amqp://guest:**@localhost:5672//

- ** .> results: redis://localhost:6379/0

- *** * config: celeryconfig

- ** .> concurrency: 4 (prefork)

- ** .> task events: OFF (enable -E to monitor tasks in this worker)

- *** - ** [queues]

- .> default exchange=direct routing_key=default

- .> math_queue exchange=math routing_key=math

[tasks]

. myapp.tasks.add

. myapp.tasks.long_running_task

[2025-10-27 10:30:00,123: INFO/MainProcess] connected to amqp://guest:**@localhost:5672//

[2025-10-27 10:30:00,456: INFO/MainProcess] mingle: searching for neighbors

[2025-10-27 10:30:01,789: INFO/MainProcess] mingle: all alone

[2025-10-27 10:30:02,012: WARNING/MainProcess] /home/user/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/celery/worker/worker.py:839: Hurr

y up, you have no running workers!

[2025-10-27 10:30:02,013: INFO/MainProcess] celery@my-machine ready.Modern Alternatives to celeryconfig.py

While celeryconfig.py works perfectly fine, the modern Python ecosystem favors more integrated and robust configuration methods.

Using a settings.py File (Django-style)

If you're using a framework like Django or just prefer to keep your settings within your main application's configuration module, you can do this.

In myapp/settings.py:

# myapp/settings.py # ... other settings like DEBUG, SECRET_KEY, etc. # Celery Settings CELERY_BROKER_URL = 'amqp://guest@localhost:5672//' CELERY_RESULT_BACKEND = 'redis://localhost:6379/0' CELERY_TASK_SERIALIZER = 'json' # ... and so on

In myapp/celery.py:

# myapp/celery.py

from celery import Celery

from . import settings # Import your settings module

app = Celery('myapp')

# Load settings from your settings.py file

# The namespace='CELERY' means Celery will only look for settings

# that start with 'CELERY_' (e.g., CELERY_BROKER_URL)

app.config_from_object('myapp.settings', namespace='CELERY')

Using Environment Variables (Best for Production)

This is the recommended approach for production environments. It decouples your configuration from your code, making it easier to manage different environments (dev, staging, prod) and using secrets managers.

You can use a library like python-decouple or django-environ.

Example with python-decouple:

-

Install the library:

pip install python-decouple -

Create a

.envfile in your project root:# .env file CELERY_BROKER_URL=amqp://guest@localhost:5672// CELERY_RESULT_BACKEND=redis://localhost:6379/0

-

In

myapp/celery.py:# myapp/celery.py from celery import Celery from decouple import config app = Celery('myapp') # Load configuration from environment variables # The 'key_prefix' tells decouple to look for 'CELERY_' prefixed variables app.conf.update( broker_url=config('CELERY_BROKER_URL'), result_backend=config('CELERY_RESULT_BACKEND'), # You can add other settings here or load from a separate section )

Summary: Which Method to Use?

| Method | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

celeryconfig.py |

Simple, explicit, easy to understand for beginners. | Less flexible, mixes config with code, not ideal for different environments. | Small projects, learning, quick prototypes. |

settings.py |

Keeps config close to the app, integrates well with frameworks like Django. | Still tied to the codebase, can become cluttered. | Django projects, medium-sized applications. |

| Environment Variables | Highly recommended for production. Secure, flexible, environment-agnostic, follows 12-factor app principles. | Requires a library like decouple, slightly more setup. |

All production deployments, containerized apps (Docker), and microservices. |