Of course! The term "pluginmanager" in Python almost always refers to the pluggy library. It is the de-facto standard for creating flexible, extensible applications using a plugin architecture.

pluggy is the engine behind major projects like pytest, tox, and Flask. It provides a clean and robust way to define an "interface" (a set of hooks) and allow other developers to write plugins that implement those hooks.

Let's break down what a plugin manager is, why it's useful, and how to use pluggy to build one.

What is a Plugin Manager?

A plugin manager is a central component in an application that is designed to be extended. Its main jobs are:

- Define a Contract: It declares a set of "hooks" or "entry points"—functions that a plugin can implement. For example, an application might have a

process_datahook. - Discover Plugins: It automatically finds and loads all the plugins that have been written for it.

- Manage the Lifecycle: It can register, unregister, and list all active plugins.

- Execute Hooks: When the application reaches a certain point (e.g., it's about to save data), it tells the plugin manager to run all registered

process_datahooks, passing the necessary data to them.

Why Use a Plugin Manager?

- Extensibility: You can add new features to your application without changing its core code. This is crucial for large projects or platforms intended for third-party developers.

- Separation of Concerns: The core application logic is separate from the plugin logic. This makes the codebase cleaner, easier to maintain, and test.

- Modularity: You can enable or disable features by simply adding or removing a plugin.

- Community & Ecosystem: It allows a community to build tools and extensions for your application (e.g., all the pytest plugins).

How to Use pluggy: A Step-by-Step Guide

Let's build a simple but complete example: a TextProcessor application that can apply various transformations to a string. We'll create a core application and a couple of plugins.

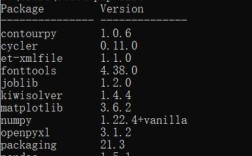

Step 1: Install pluggy

First, you need to install the library:

pip install pluggy

Step 2: The Core Application (app.py)

This is the main application that will use the plugin manager. It will define the hooks and orchestrate the process.

# app.py

import pluggy

# 1. Define a "hookspec" (the contract for plugins)

# This is an interface that plugins can implement.

# We use a class with @pluggy.spec to define the hooks.

class TextProcessorHooks:

"""Hooks for processing text."""

@pluggy.spec

def process_text(self, text: str) -> str:

"""

Hook to modify the input text.

:param text: The original text string.

:return: The modified text string.

"""

# This is a default implementation. If a plugin doesn't

# override this, this version will be called.

return text

# 2. Create a PluginManager instance

# We pass our hookspec class to it.

plugin_manager = pluggy.PluginManager("text_processor")

plugin_manager.add_hookspecs(TextProcessorHooks)

# 3. The core application logic

def main():

original_text = "Hello, World! This is a test."

print(f"Original text: '{original_text}'\n")

# Load plugins (we'll create these next)

plugin_manager.register(plugins.UpperCasePlugin())

plugin_manager.register(plugins.ReversePlugin())

# You can also register modules or entry points:

# plugin_manager.load_setuptools_entrypoints("my_app.plugins")

# 4. Call the hook for all registered plugins

# The plugin manager will call the `process_text` method

# on each plugin, passing the result of the previous one.

processed_text = original_text

for result in plugin_manager.hook.process_text(processed_text):

processed_text = result

print(f"Final processed text: '{processed_text}'")

# You can see which plugins are registered

print("\nRegistered plugins:")

for plugin in plugin_manager.list_plugin_distinfo():

print(f"- {plugin.project_name} v{plugin.version}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

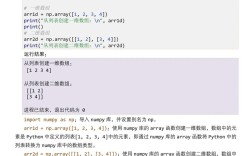

Step 3: Create the Plugins (plugins/ directory)

Now, let's create the plugins in a directory named plugins. Each plugin is just a Python class that implements the hook methods.

File: plugins/__init__.py

# This file makes 'plugins' a Python package

File: plugins/uppercase.py

# plugins/uppercase.py

class UpperCasePlugin:

"""A plugin that converts text to uppercase."""

# The method name MUST match the hookspec name: `process_text`

def process_text(self, text: str) -> str:

print(f" [UpperCasePlugin] Processing: '{text}'")

return text.upper()

File: plugins/reverse.py

# plugins/reverse.py

class ReversePlugin:

"""A plugin that reverses the text."""

def process_text(self, text: str) -> str:

print(f" [ReversePlugin] Processing: '{text}'")

return text[::-1]

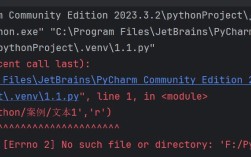

Step 4: Run the Application

Your directory structure should look like this:

my_project/

├── app.py

└── plugins/

├── __init__.py

├── uppercase.py

└── reverse.pyNow, run the app.py script:

python app.py

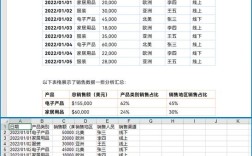

Expected Output:

Original text: 'Hello, World! This is a test.'

[UpperCasePlugin] Processing: 'Hello, World! This is a test.'

[ReversePlugin] Processing: 'HELLO, WORLD! THIS IS A TEST.'

Final processed text: '!TSET A SI SIHT !DLROW ,OLLEH'

Registered plugins:

- text_processor v0.1 (from the plugin_manager name)Key Concepts Explained

@pluggy.spec: This decorator on a method in a class turns that class into a "hookspec". It defines the official API that plugins are expected to follow.PluginManager: The central object. It manages the lifecycle of plugins and knows how to call the hooks.plugin_manager.register(): This tells the manager about a specific plugin instance. The plugin instance must have methods that match the hookspec names.plugin_manager.hook.process_text(...): This is the magic. When you access an attribute ofplugin_manager.hook, you get a specialHookCallerobject. Calling it executes the corresponding method (process_text) on all registered plugins.- Result Handling: By default,

pluggycollects the return value of each hook and returns them as a list. In our example, we use aforloop to chain the results: the output of one plugin becomes the input for the next.

Advanced pluggy Features

pluggy is more powerful than our simple example shows:

- Hook Wrappers (

@hookspec(wrapper=True)): Allows a plugin to wrap the execution of other plugins. It can run code before and after the hook is called, and even modify arguments or results. This is used bypytestfor its famouspytest_runtest_makereporthook. - Call Sub-Execution (

firstresult=True): Sometimes you only want the first plugin that returns a non-Noneresult to "win". You can specify this in the hookspec.@pluggy.spec(firstresult=True) def get_greeting(self) -> str: """Get a greeting from a plugin.""" ...In this case, the plugin manager would stop calling other plugins as soon as one returns a string.

- Loading Plugins from Entry Points: For large, distributable applications, you don't want to manually register plugins. Instead, you can define them in your

setup.pyorpyproject.tomlfiles.pluggycan automatically discover and load them using setuptools' entry points mechanism.

Alternatives to pluggy

While pluggy is the most popular, other approaches exist:

stevedore: A library from the OpenStack project. It's more heavyweight and focuses on managing plugins as Python modules or entry points, often with lifecycle management (start/stop). It's a good choice if you need more than just hook calling.- Manual Implementation: You could build a simple plugin system yourself using Python's

importlibto find modules in a directory and inspect them for functions or classes with a specific naming convention. This is good for learning but becomes complex for large-scale applications.

Conclusion:

For almost any new project in Python that requires a plugin architecture, pluggy is the recommended choice. It's lightweight, well-documented, battle-tested by major projects, and provides a clean, Pythonic way to create extensible software