Of course! The with open(...) statement is a fundamental and highly recommended way to handle files in Python. Let's break it down completely.

The Core Idea: "Why with open?"

Imagine you're opening a file. The computer needs to find the file on the disk, reserve a small amount of memory to manage it, and keep track of whether it's open or not.

When you're done, you must close the file. This tells the computer, "I'm finished with this file, you can release the memory and the file lock."

The problem is, what if an error happens while you're reading the file? Your program might crash, and the close() command would never run. This can lead to problems:

- Resource Leaks: The file remains "open" in the system, wasting memory.

- Data Corruption: If you were writing to the file and the program crashed, the data might be left in an incomplete or corrupted state.

with open(...) solves this automatically. It's a context manager. It guarantees that the file will be closed, no matter what—even if an error occurs inside the with block. This is often called "exception-safe" file handling.

The Basic Syntax

with open(filename, mode) as file_object:

# Do something with the file_object here

# (e.g., read from it or write to it)

# The file is automatically closed when the block is exited

Let's break down the parts:

with: This is the keyword that starts the context manager.open(...): This is the built-in Python function that actually opens the file.filename: A string representing the path to your file.mode: A string that specifies what you want to do with the file (read, write, append, etc.).as file_object: This assigns the opened file to a variable (in this case,file_object). You will use this variable to interact with the file's contents.- The colon and the indented block: This is the standard Python syntax for a block of code. All the operations you want to perform on the file go inside this block.

File Modes (mode)

The mode argument is crucial. Here are the most common ones:

| Mode | Description |

|---|---|

'r' |

Read (default). Opens a file for reading. Fails if the file doesn't exist. |

'w' |

Write. Opens a file for writing. Creates the file if it doesn't exist, or overwrites it if it does. |

'a' |

Append. Opens a file for appending. Creates the file if it doesn't exist. Data written is added to the end. |

'r+' |

Read and Write. Opens a file for both reading and writing. The file pointer is at the beginning. |

'b' |

Binary. Used for non-text files (like images, PDFs, etc.). Can be combined with others: 'rb', 'wb', 'ab'. |

't' |

Text (default). Used for text files. Can be combined: 'rt'. |

Practical Examples

Let's assume we have a file named my_file.txt with the following content:

Hello, world!

This is the second line.

This is the third line.Example 1: Reading a File ('r')

This is the most common use case.

# The 'r' mode is the default, so you can omit it.

with open('my_file.txt', 'r') as f:

# Read the entire file content into a single string

content = f.read()

print(content)

# --- Output ---

# Hello, world!

# This is the second line.

# This is the third line.

Alternative ways to read:

# --- Read line by line ---

with open('my_file.txt', 'r') as f:

print("--- Reading line by line ---")

line1 = f.readline()

print(line1) # Prints "Hello, world!\n"

line2 = f.readline()

print(line2) # Prints "This is the second line.\n"

# --- Read all lines into a list ---

with open('my_file.txt', 'r') as f:

print("\n--- Reading all lines into a list ---")

all_lines = f.readlines()

print(all_lines)

# Output: ['Hello, world!\n', 'This is the second line.\n', 'This is the third line.\n']

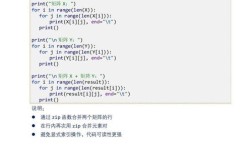

# --- The best way: loop over the file object ---

# This is memory-efficient for large files as it doesn't load everything at once.

with open('my_file.txt', 'r') as f:

print("\n--- Looping over the file object ---")

for line in f:

# The 'end' argument prevents print() from adding an extra newline

# because each line from the file already has one.

print(line, end='')

Example 2: Writing to a File ('w')

Warning: 'w' mode will overwrite the file if it already exists.

# This will create a new file named 'new_file.txt' or overwrite it if it exists.

with open('new_file.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write("This is the first line of the new file.\n")

f.write("This is the second line.\n")

# Now, if you open 'new_file.txt', its content will be exactly what we wrote.

Example 3: Appending to a File ('a')

This adds content to the end of an existing file without deleting it.

# Let's add a line to our original 'my_file.txt'

with open('my_file.txt', 'a') as f:

f.write("This is a new line appended at the end.\n")

# Now, if you read 'my_file.txt', the last line will be the one we just added.

Handling File Paths (Crucial!)

If your file is not in the same directory as your Python script, you need to provide the full path.

- Windows: Use double backslashes

\\or a raw stringr'...'. - macOS / Linux: Use forward slashes .

# Windows example

# Using a raw string (r'...') is the best practice to avoid issues with backslashes.

file_path = r'C:\Users\YourUser\Documents\data.csv'

with open(file_path, 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

# macOS / Linux example

file_path = '/home/user/documents/data.csv'

with open(file_path, 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

For more robust path handling, especially across different operating systems, it's highly recommended to use the pathlib module (available in Python 3.4+).

from pathlib import Path

# Creates a path object that works on any OS

# Path('.') means the current directory

file_path = Path('.') / 'my_file.txt'

with open(file_path, 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

print(content)

The Old Way (Not Recommended)

To understand why with open is better, here's the old way of doing it:

# DO NOT DO THIS!

f = open('my_file.txt', 'r')

try:

content = f.read()

print(content)

finally:

f.close()

This try...finally block does the same thing as with open: it ensures f.close() is called. However, with open is much cleaner, more readable, and less error-prone. It's the modern, standard, and Pythonic way to handle files.