Of course! Let's dive deep into metaclasses in Python 2.7. This is an advanced topic, but understanding it gives you incredible power over how classes are created.

The Big Picture: What is a Metaclass?

Think of it this way:

- An object is an instance of a class.

my_object = MyClass()->my_objectis an instance ofMyClass.

- A class is an instance of a metaclass.

MyClass = MetaClass()->MyClassis an instance ofMetaClass.

In short, a metaclass is a "class factory". It's the class that creates classes. When you write a class statement, Python calls the metaclass to build that class object.

By default, Python uses a built-in metaclass called type. So when you write:

class MyClass(object):

pass

Python is essentially doing this behind the scenes:

MyClass = type('MyClass', (object,), {})

'MyClass': The name of the new class.(object,): The tuple of base classes (the "parents").- The dictionary of attributes and methods for the new class.

A metaclass is simply a custom class that inherits from type and lets you hook into this creation process.

The Syntax for a Metaclass in Python 2.7

This is a key difference from Python 3. In Python 2.7, you don't pass the metaclass argument in the class definition. Instead, you define a class attribute named __metaclass__.

# In Python 2.7

class MyClass(object):

__metaclass__ = MyMetaClass

# ... class body ...

When Python sees __metaclass__ in the class body, it knows to use MyMetaClass as the factory for creating MyClass.

How to Create a Metaclass: The __new__ Method

A metaclass is most commonly defined by overriding the __new__ method. This method is called before __init__ and is responsible for creating and returning the new class object.

The signature for __new__ in a metaclass is:

def __new__(meta, name, bases, dct):

# meta: The metaclass itself (e.g., MyMetaClass)

# name: The name of the class being created (e.g., 'MyClass')

# bases: A tuple of the base classes (e.g., (object,))

# dct: The dictionary of the class's attributes and methods

Let's see a simple, practical example.

Example 1: The "Logger" Metaclass

Imagine you want to automatically log every time a method from a specific class is called. A metaclass is a perfect way to achieve this without modifying every single method.

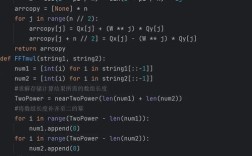

import time

# 1. Define the metaclass

class LoggedMeta(type):

"""A metaclass that logs the creation of a new class and its method calls."""

def __new__(meta, name, bases, dct):

print "Creating class: %s" % name

# We will wrap each method with a logging function

for key, value in dct.items():

# We only care about methods (callable attributes)

if callable(value):

# Create a new wrapper function

def method_wrapper(method_self, *args, **kwargs):

print "Calling method: %s" % method_self.__class__.__name__ + "." + method.__name__

start_time = time.time()

result = method(self=method_self, *args, **kwargs) # Call the original method

end_time = time.time()

print "Method %s finished in %f seconds" % (method.__name__, end_time - start_time)

return result

# Crucial: We need to preserve the original method's name and docstring

method_wrapper.__name__ = value.__name__

method_wrapper.__doc__ = value.__doc__

# Replace the original method in the class dictionary with our wrapper

dct[key] = method_wrapper

# Let the 'type' class do the actual class creation

return super(LoggedMeta, meta).__new__(meta, name, bases, dct)

# 2. Use the metaclass by setting __metaclass__

class MyClass(object):

__metaclass__ = LoggedMeta

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

print "MyClass instance created with x = %s" % self.x

def do_something(self):

"""This is a method that does something."""

print "Doing something with x = %s" % self.x

time.sleep(1) # Simulate work

return self.x * 2

# 3. Create an instance and use it

print "-" * 20

my_instance = MyClass(10)

print "-" * 20

result = my_instance.do_something()

print "-" * 20

print "Result:", result

Output:

Creating class: MyClass

--------------------

MyClass instance created with x = 10

--------------------

Calling method: MyClass.do_something

Doing something with x = 10

Method do_something finished in 1.000123 seconds

--------------------

Result: 20As you can see, the LoggedMeta class intercepted the creation of MyClass, found its methods (__init__ and do_something), and wrapped them with logging functionality, all without us touching the methods themselves.

A More Practical Example: enforcing an interface

Let's say you have a base class Plugin and you want to ensure that any class inheriting from it implements a run() method. A metaclass can enforce this at class definition time, raising an error if the method is missing.

# 1. Define the metaclass

class EnforcerMeta(type):

"""A metaclass that enforces the presence of a 'run' method."""

def __new__(meta, name, bases, dct):

# Check if this class is a direct subclass of Plugin

# We don't want to enforce this on Plugin itself

is_plugin_subclass = any(base.__name__ == 'Plugin' for base in bases)

if is_plugin_subclass and 'run' not in dct:

raise TypeError("Class '%s' must implement the 'run()' method because it inherits from Plugin." % name)

return super(EnforcerMeta, meta).__new__(meta, name, bases, dct)

# 2. Define the base class, using the metaclass

class Plugin(object):

__metaclass__ = EnforcerMeta

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# 3. Define a GOOD subclass

class GoodPlugin(Plugin):

def __init__(self, name):

super(GoodPlugin, self).__init__(name)

def run(self):

print "Running GoodPlugin:", self.name

# 4. Define a BAD subclass (this will fail at class definition time)

try:

class BadPlugin(Plugin):

def __init__(self, name):

super(BadPlugin, self).__init__(name)

# Missing the 'run' method!

except TypeError as e:

print "Error creating BadPlugin:", e

# 5. Test the good plugin

g = GoodPlugin("My Good Plugin")

g.run()

Output:

Error creating BadPlugin: Class 'BadPlugin' must implement the 'run()' method because it inherits from Plugin.

Running GoodPlugin: My Good PluginThis catches errors immediately when the class is defined, which is much better than waiting for someone to try to use the BadPlugin and get an AttributeError.

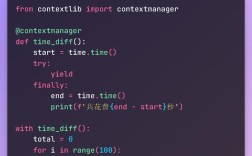

The __init__ Method of a Metaclass

Just like a regular class has an __init__ method to initialize its instances, a metaclass can have an __init__ method to initialize the class after it has been created.

__new__: Creates the class object.__init__: Initializes the class object.

class MyMeta(type):

def __new__(meta, name, bases, dct):

print "__new__: Creating the class object '%s'" % name

return super(MyMeta, meta).__new__(meta, name, bases, dct)

def __init__(cls, name, bases, dct):

# 'cls' is the class that was just created (e.g., MyClass)

print "__init__: Initializing the class object '%s'" % name

super(MyMeta, cls).__init__(name, bases, dct)

# You can now add attributes to the class itself

cls.created_at = "right now"

class MyClass(object):

__metaclass__ = MyMeta

print "-" * 10

print "MyClass attribute 'created_at':", MyClass.created_at

Output:

__new__: Creating the class object 'MyClass'

__init__: Initializing the class object 'MyClass'

----------

MyClass attribute 'created_at': right now