Of course! Let's dive deep into BlockingQueue in Java. It's a fundamental and incredibly useful interface in the java.util.concurrent package.

What is a BlockingQueue?

A BlockingQueue is a thread-safe queue that additionally supports operations that wait for the queue to become non-empty when retrieving an element, and wait for space to become available when storing an element.

Think of it as a bridge between producer and consumer threads. Producers add elements to the queue, and consumers take them off. The "blocking" part is what makes it so powerful for concurrent programming: if a consumer tries to take an element from an empty queue, it will block (wait) until a producer adds one. Similarly, if a producer tries to add an element to a full queue, it will block until a consumer makes space.

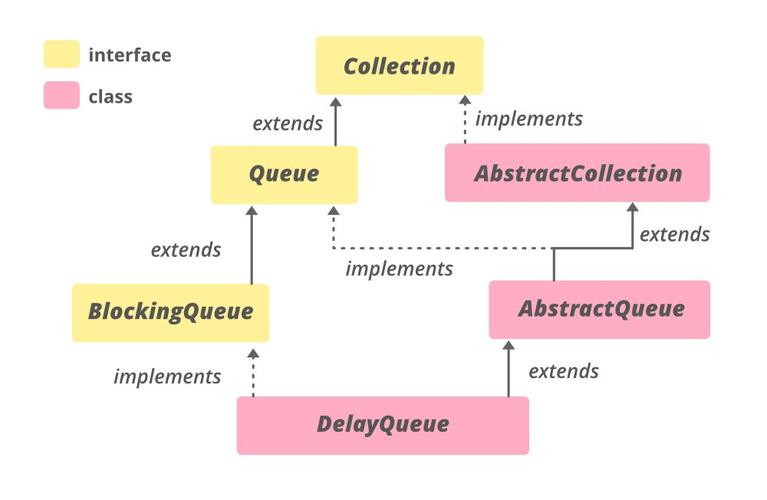

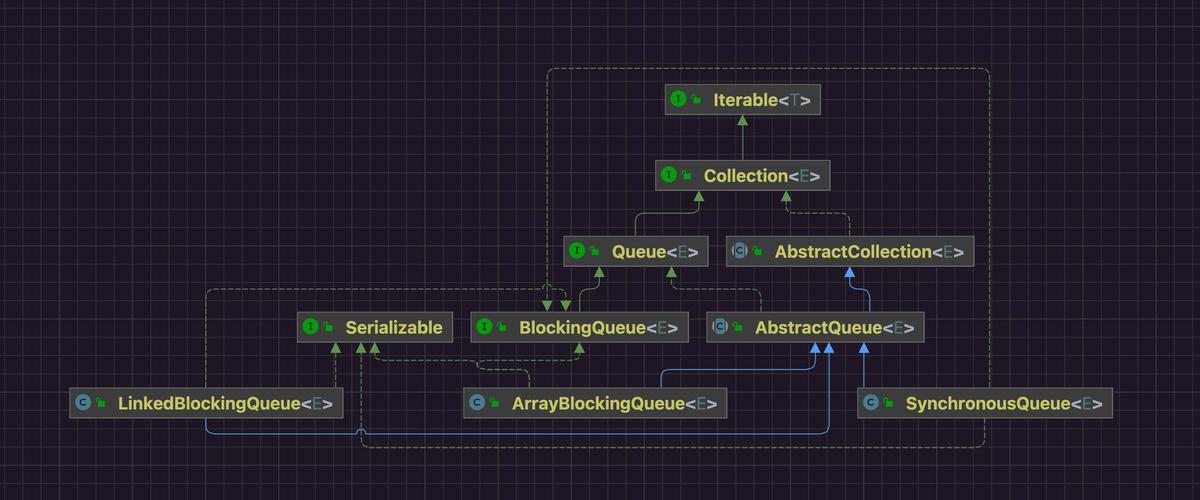

Key Interfaces and Hierarchy

BlockingQueue is an interface. You'll typically use one of its concrete implementations.

java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue (Interface)

^

|

+------------------+------------------+------------------+

| | | |

ArrayBlockingQueue LinkedBlockingQueue PriorityBlockingQueue DelayQueue

(Sized, FIFO) (Sized, FIFO) (Priority-based) (Delayed elements)

| |

+------------------+

|

SynchronousQueue

(Rendezvous point, no capacity)Core Methods

The methods in BlockingQueue are designed for different blocking and non-blocking scenarios.

| Method Type | Throws Exception | Special Value | Blocks | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insert | add(e) |

offer(e) |

put(e) |

Adds an element to the tail of the queue. add() throws IllegalStateException if full. offer() returns false if full. put() blocks until space is available. |

offer(e, time, unit) |

Attempts to add an element, blocking for up to the specified time before giving up. Returns true on success, false on timeout. |

|||

| Remove | remove() |

poll() |

take() |

Retrieves and removes an element from the head. remove() throws NoSuchElementException if empty. poll() returns null if empty. take() blocks until an element is available. |

poll(time, unit) |

Attempts to retrieve an element, blocking for up to the specified time. Returns the element or null on timeout. |

|||

| Examine | element() |

peek() |

Retrieves, but does not remove, the head element. element() throws NoSuchElementException if empty. peek() returns null if empty. Neither blocks. |

Most Common Methods:

put(e): The go-to for producers. It will block until the queue has capacity.take(): The go-to for consumers. It will block until the queue has an element.offer(e): Useful for producers that don't want to block and can handle a "full" state gracefully.poll(): Useful for consumers that don't want to block and can handle an "empty" state gracefully.

Common Implementations

ArrayBlockingQueue

- Backed by an array.

- Has a fixed capacity specified during creation.

- Uses a single lock for both producers and consumers (can lead to contention).

- Use Case: When you know the maximum size of your queue and want to prevent it from growing uncontrollably.

// A queue that can hold a maximum of 10 items BlockingQueue<String> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(10);

LinkedBlockingQueue

- Backed by a linked nodes.

- Has an optional capacity. If no capacity is specified, it can grow to

Integer.MAX_VALUE. - Uses separate locks for producers and consumers (higher throughput than

ArrayBlockingQueue). - Use Case: The most common choice. Use it when you need a flexible-sized queue or expect high throughput.

// A queue with no theoretical maximum size (practically very large) BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>(); // A queue with a maximum of 100 items BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>(100);

PriorityBlockingQueue

- Backed by a priority heap.

- Elements are not retrieved in FIFO order, but in priority order (defined by

Comparableor aComparator). - Has no fixed capacity and will grow as needed.

- Use Case: When you need to process elements based on their priority (e.g., processing high-priority tasks first).

// A queue of tasks, where tasks with higher priority are processed first BlockingQueue<Runnable> queue = new PriorityBlockingQueue<>();

SynchronousQueue

- A special case with no capacity.

- It's a rendezvous point. A

putto the queue will block until another thread does atake, and vice-versa. It's not really a queue at all, but a hand-off mechanism. - Use Case: Directly handing off items from a producer to a consumer without intermediate storage. Used internally by

Executors.newCachedThreadPool().

// A queue where each put must be matched by a take before another put can proceed BlockingQueue<Integer> queue = new SynchronousQueue<>();

Classic Producer-Consumer Example

This is the canonical use case for BlockingQueue. We'll create a shared queue and two separate threads: a Producer and a Consumer.

import java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue;

import java.util.concurrent.LinkedBlockingQueue;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class ProducerConsumerExample {

// Shared bounded queue

private static final BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>(5);

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create and start the producer and consumer threads

Thread producerThread = new Thread(new Producer());

Thread consumerThread = new Thread(new Consumer());

producerThread.start();

consumerThread.start();

// Let them run for a bit

try {

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(10);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

// Stop the threads (in a real app, you'd use a more robust shutdown mechanism)

producerThread.interrupt();

consumerThread.interrupt();

}

static class Producer implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

int i = 0;

try {

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

String item = "Item-" + i++;

System.out.println("Producing: " + item);

// put() will block if the queue is full

queue.put(item);

// Simulate production time

Thread.sleep(500);

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println("Producer interrupted.");

Thread.currentThread().interrupt(); // Restore the interrupt status

}

System.out.println("Producer finished.");

}

}

static class Consumer implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

// take() will block if the queue is empty

String item = queue.take();

System.out.println("Consuming: " + item);

// Simulate consumption time

Thread.sleep(1000);

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println("Consumer interrupted.");

Thread.currentThread().interrupt(); // Restore the interrupt status

}

System.out.println("Consumer finished.");

}

}

}

How it works:

- The

Producercreates items and usesqueue.put(item). If the queue is full,put()pauses the producer thread until theConsumermakes space. - The

Consumerusesqueue.take()to get items. If the queue is empty,take()pauses the consumer thread until theProduceradds an item. - This elegant synchronization is handled entirely by the

BlockingQueue, eliminating the need for manualwait()andnotify()calls, complexsynchronizedblocks, and messy state variables.

When to Use BlockingQueue

- Producer-Consumer Patterns: The primary use case. Any time you have one or more threads producing work and one or more threads consuming it.

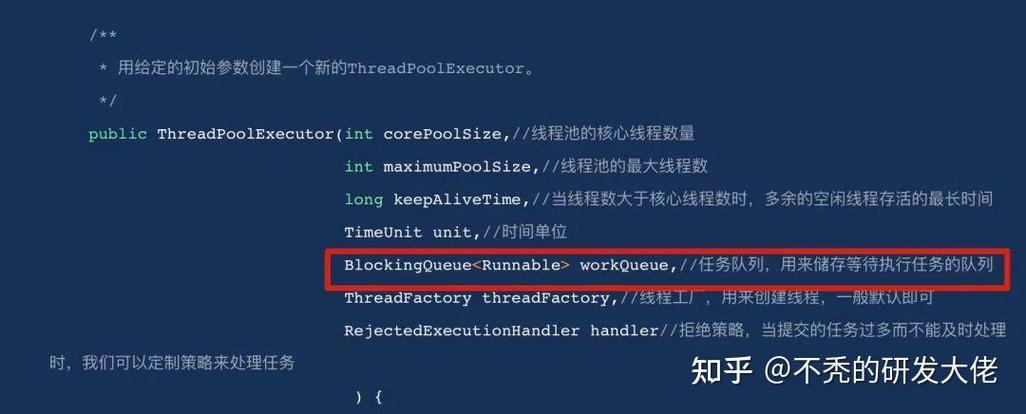

- Task Execution: Thread pools (like

ExecutorService) often useBlockingQueueto hold tasks waiting to be executed by worker threads. - Event-Driven Architectures: For queuing events from multiple sources to be processed by a single handler.

- Data Pipelines: To buffer data between different stages of a multi-stage processing pipeline.

Advantages

- Simplicity: Dramatically simplifies concurrent code.

- Thread-Safety: It's inherently thread-safe, so you don't have to worry about race conditions.

- Efficiency: The implementations are highly optimized for concurrent access.

- Robustness: Prevents common errors like losing notifications or having to write complex, error-prone synchronization logic.