Of course. Let's "dive into" Python 2. This is a fascinating journey because understanding Python 2 is key to understanding the history of Python and the major philosophical shift that led to Python 3.

This guide will cover the core concepts, the "Pythonic" way of thinking in version 2, and its crucial differences from Python 3.

Part 1: The Historical Context - Why Python 2 Existed

Python 2.0 was released in 2000. For over a decade, it was the dominant, stable, and widely adopted version of Python. It powered a massive portion of the early web, from startups to tech giants. Its design philosophy, famously summarized in "The Zen of Python" (import this), prioritized backward compatibility and pragmatism.

However, as Python grew, its creators realized some fundamental design decisions made in version 2 were holding back the language's future. This led to the "great schism" and the creation of Python 3 in 2008, which was designed to be cleaner, more consistent, and better for internationalization.

The most critical difference between Python 2 and Python 3 is how they handle text. This is the single most important concept you must grasp.

Part 2: The Core Concepts of Python 2

Let's explore the syntax and features that define Python 2.

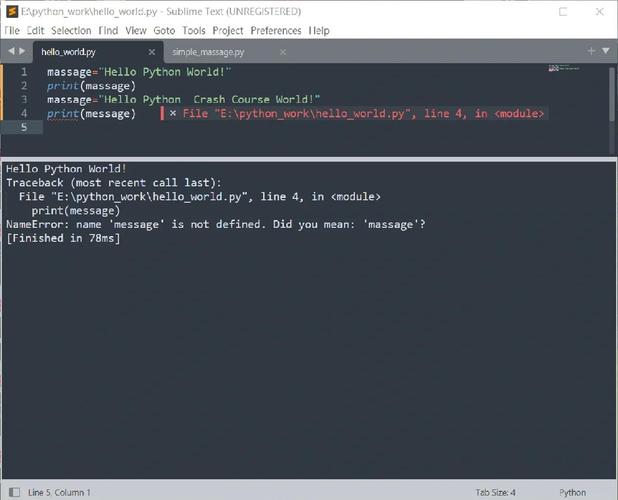

The print Statement (Not a Function!)

In Python 2, print was a keyword, a statement, not a function. This means you don't use parentheses.

# Python 2

print "Hello, world!"

print "The answer is", 42

# This would be a SyntaxError in Python 2

# print("Hello, world!")

You could also "trick" it into behaving like a function by using the __future__ import, which is a common sight in codebases transitioning to Python 3.

# Python 2 (with a forward-looking import)

from __future__ import print_function

# Now this works, but it's still Python 2 code

print("Hello, world!")

Integer Division: The Classic "Gotcha"

This is the most infamous "bug" or feature of Python 2. When you divide two integers, you get an integer. The decimal part is simply truncated (chopped off).

# Python 2 >>> 5 / 2 2 # Not 2.5! >>> 7 / 3 2 >>> -5 / 2 -2 # It truncates towards zero, not floor division.

To get a floating-point result, you had to make sure at least one of the numbers was a float.

# Python 2 >>> 5.0 / 2 2.5 >>> 5 / 2.0 2.5

Why did it do this? For historical reasons, it mimicked the behavior of C and other low-level languages, which was considered pragmatic at the time. This was a major source of bugs for new programmers.

Unicode vs. Bytes: The Text vs. Data Dichotomy

This is the most fundamental and important difference. In Python 2, there were two main string types:

str: A sequence of bytes. This is the default string type. It has no inherent encoding. It's just raw data.unicode: A sequence of abstract Unicode characters. This is what you should use for text that needs to handle international characters (like ,你, ).

The Golden Rule of Python 2:

stris bytes.unicodeis text.

You must explicitly convert between them using an encoding (almost always UTF-8).

Example: The Pain of Python 2 Strings

# Python 2

# A string of bytes

my_bytes = "hello"

# A string of text

my_unicode = u"hello"

# This works fine if you're only in ASCII

print my_bytes == my_unicode # True

# --- The Problem ---

# Let's add an accented character, 'é'

my_unicode_text = u"café"

my_bytes_data = "café" # This is just 5 bytes: c, a, f, e, with an acute accent

# This will FAIL with a UnicodeDecodeError because you're trying to compare

# bytes to text without telling Python how to decode the bytes.

# print my_bytes_data == my_unicode_text

# You MUST decode the bytes to unicode first

decoded_text = my_bytes_data.decode('utf-8')

print decoded_text == my_unicode_text # True

# And you MUST encode unicode to bytes to write it to a file or send over a network

bytes_to_write = my_unicode_text.encode('utf-8')

This constant dance between str and unicode was a major source of bugs and confusion. It was easy to forget an encoding and have your program crash or, worse, corrupt data silently.

range() vs. xrange()

In Python 2, range() would generate a full list of numbers in memory. If you did range(1000000), it would create a list with one million integers in RAM.

# Python 2 # This creates a real list in memory big_list = range(1000000) print type(big_list) # <type 'list'>

To save memory, Python 2 introduced xrange(). It returns an xrange object, which is a "sequence type" that generates numbers on-the-fly (it's a "generator"). It doesn't store the whole list in memory.

# Python 2 # This is memory-efficient big_range = xrange(1000000) print type(big_range) # <type 'xrange'>

In Python 3, range() was redesigned to behave like xrange(), and xrange() was removed.

Dictionary Iteration (.iteritems(), .iterkeys(), .itervalues())

In Python 2, if you iterated over a dictionary, you got its keys. To get key-value pairs, you used .iteritems().

# Python 2

my_dict = {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}

# Iterating over keys

for key in my_dict:

print key

# Iterating over key-value pairs (memory-efficient)

for key, value in my_dict.iteritems():

print key, value

.iteritems() returns an iterator, which is more memory-efficient than .items(), which would create a full list of tuples.

In Python 3, .iteritems() was removed, and .items() now returns an iterator-like view, making it the default.

Part 3: The "Python 2" Way of Thinking

A Python 2 programmer's mindset was one of explicit control and managing trade-offs.

- Memory vs. Convenience: You had to choose between

range()(convenient but memory-heavy) andxrange()(memory-efficient but slightly more verbose). You had to choose between.items()(simple) and.iteritems()(fast for large dicts). - Explicit Encoding: You were constantly aware that

strwas bytes. You had to make a conscious decision to useunicodefor text and to explicitly encode/decode it when interacting with the outside world (files, network, databases). This was tedious but made the data flow explicit. - "It Works, Therefore It's Okay": The integer division "gotcha" was a perfect example of this pragmatic, but potentially error-prone, philosophy. If you knew the rule, you could write code that worked quickly. If you didn't, you'd get strange bugs.

Part 4: Why You Should (or Shouldn't) Learn Python 2 Today

Reasons to Learn Python 2:

- Maintaining Legacy Code: Many systems, especially in scientific computing, finance, and large corporations, still run on Python 2. If you need to fix a bug or add a feature, you must know Python 2.

- Understanding History: It helps you appreciate the design decisions made in Python 3. You'll understand why

print()is a function, why integer division behaves differently, and why there's no longer astrvs.unicodedistinction. - The

__future__Module: Reading code that usesfrom __future__ import ...is common. Understanding what those imports do (e.g.,print_function,absolute_import) is a valuable skill.

Reasons NOT to Learn Python 2 as a Beginner:

- It's Obsolete: The Python community has fully migrated to Python 3. All new libraries, frameworks, and tools are developed for Python 3.

- Bad Habits: Learning Python 2 first will teach you habits that are considered incorrect or outdated in the modern Python world (e.g., using the old

printstatement, relying on integer division quirks). - No Official Support: Python 2 reached its "end of life" on January 1, 2025. It no longer receives security updates or bug fixes. Running it in production is a security risk.

Conclusion: The Dive is Over

Diving into Python 2 is like exploring a historical monument. It's fascinating to see how the language was shaped, but you wouldn't want to build a new house with its blueprints.

The core takeaway is that Python 2 was a product of its time, balancing pragmatism with the growing pains of a global language. Its legacy lives on in the careful, consistent design of Python 3. By understanding Python 2, you gain a deeper appreciation for the power and clarity of modern Python.