Of course. The statement "Python is inconsistent" is a common sentiment, especially from developers coming from more rigid languages like Java or C#. However, it's more accurate to say that Python often prioritizes practicality and readability over strict, dogmatic consistency.

Let's break down the different areas where this "inconsistency" is most often felt, why it exists, and whether it's a flaw or a feature.

Naming Conventions: The snake_case vs. camelCase vs. PascalCase Mess

This is the most famous example of perceived inconsistency. Python's own standard library is a mix of styles.

| Style | Usage | Examples | Why it's "inconsistent" |

|---|---|---|---|

snake_case |

The de facto standard for variables, functions, and methods. | my_variable, calculate_total, open_file() |

This is what you should do 99% of the time. It's readable and avoids camelCase ambiguity. |

PascalCase |

Standard for class names. | MyClass, HttpResponse, DatabaseConnection |

Follows the convention from other object-oriented languages. Easy to distinguish from functions. |

camelCase |

Used in some special cases, mostly in older code or specific contexts. | Pygments, PyYAML, tkinter.Tcl |

This is the main point of contention. Why not stick to one style? |

Why does this exist?

- Historical Reasons: The

camelCasein libraries likeTkintercomes from the underlying Tcl/Tk library it was wrapping. Python didn't invent these components; it integrated them. - PEP 8 (The Style Guide): PEP 8 recommends

snake_casebut doesn't forbid others. It acknowledges that consistency within a project is more important than a universal rule. The goal is to avoid "visual noise" from constantly switching styles. - The "Explicit is better than implicit" Rule: The argument could be made that

getHTTPResponse()is ambiguous (isHTTPone word or three?).get_http_response()is explicit and unambiguous.

Is it a flaw? For newcomers, it's confusing. For experienced developers, it's a minor quirk. The community strongly enforces snake_case for new code, so this inconsistency is mostly historical.

"Magic" Methods and Dunder Names

Methods that start and end with double underscores (__dunder__) are often called "magic methods" or "special methods." Their behavior can feel inconsistent.

| Method | What it does | Why it feels inconsistent |

|---|---|---|

__len__(self) |

len(my_object) |

This makes sense. It returns the "length." |

__str__(self) |

str(my_object) or print(my_object) |

Returns a "user-friendly" string representation. |

__repr__(self) |

repr(my_object) or in a REPL |

Returns an "official," unambiguous developer representation. Ideally, eval(repr(obj)) == obj. |

__add__(self, other) |

my_object + other |

Defines the operator. |

__iadd__(self, other) |

my_object += other |

Defines the in-place operator. |

__call__(self, ...) |

my_object(...) |

Makes an instance of a class callable like a function. |

Why does this exist? This is a form of operator overloading and polymorphism. It allows different objects to respond to the same built-in functions or operators in their own logical way. A list another list concatenates them. A number another number adds them. A string another string concatenates them. This is powerful, not inconsistent.

The "magic" comes from the fact that you don't call my_object.__add__(other); you just use the clean my_object + other syntax. The dunder names prevent name collisions with normal methods.

Is it a flaw? It can be overwhelming for beginners, but it's a core feature of Python's object model, enabling elegant and readable code.

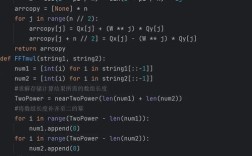

Mutable Default Arguments (The "Gotcha")

This is a classic and very real pitfall for new Python developers.

def add_to_list(item, my_list=[]):

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(add_to_list(1))

# Output: [1]

print(add_to_list(2))

# Output: [1, 2] # Wait, what? Why is the old list still there?

Why does this happen?

The default argument my_list=[] is evaluated only once when the function is defined, not every time it's called. So, all subsequent calls to the function reuse that exact same list object.

The "consistent" way to do it:

The correct and "Pythonic" way is to use None as a default and create a new list inside the function.

def add_to_list_fixed(item, my_list=None):

if my_list is None:

my_list = []

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(add_to_list_fixed(1))

# Output: [1]

print(add_to_list_fixed(2))

# Output: [2] # This works as expected.

Why is it designed this way? This behavior is a direct consequence of a core Python principle: "Arguments are evaluated at the point of call." The default values are part of the function's definition, so they are evaluated at definition time. While this leads to the "gotcha," it's a consistent application of that rule.

Is it a flaw? Many argue it is. Guido van Rossum (Python's creator) has called it a "mistake." However, changing it now would break a massive amount of existing code. The fix is simply to learn the idiom and avoid mutable defaults.

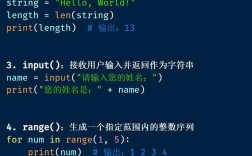

Slicing and Indexing

Python's slicing is powerful but can feel inconsistent with how other languages handle indices.

my_list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'] # Positive indices print(my_list[0]) # 'a' (starts at 0) print(my_list[4]) # 'e' # Negative indices (count from the end) print(my_list[-1]) # 'e' print(my_list[-2]) # 'd' # Slicing: [start:stop:step] print(my_list[1:4]) # ['b', 'c', 'd'] (stops *before* index 4) print(my_list[::2]) # ['a', 'c', 'e'] (steps by 2) print(my_list[::-1]) # ['e', 'd', 'c', 'b', 'a'] (reverses the list)

Why does this exist?

- 0-based indexing: This is a legacy from C and is standard in most modern programming languages.

- Slicing is "half-open":

[start:stop]includes thestartindex but excludes thestopindex. This makes slicing operations clean and predictable. For example,my_list[0:3]gives you the first three elements, andmy_list[3:6]gives you the next three, with no overlap. - Negative indices and

[::-1]for reversal: These are incredibly convenient features that are hard to replicate elegantly in other languages.

Is it a flaw? Once you understand the logic (especially the half-open interval), it becomes incredibly powerful and consistent within its own system. It's just different from what some developers expect.

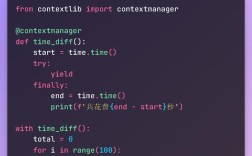

Types: Dynamic, but sometimes not

Python is dynamically typed, but it has static typing capabilities (via mypy and type hints).

# Dynamic Typing

x = 10

print(type(x)) # <class 'int'>

x = "hello"

print(type(x)) # <class 'str'>

# Static Typing (with type hints)

def greet(name: str) -> str:

return f"Hello, {name}"

# The type hints are not enforced at runtime by default

greet(123) # This will not cause an error, but mypy will catch it.

Why does this exist?

- Dynamic Typing: Offers flexibility and rapid development. You don't have to specify types for everything, which speeds up prototyping.

- Type Hints: Added to improve code readability, enable static analysis (catching errors before runtime), and support better IDE autocompletion and refactoring. They are an opt-in feature.

Is it a flaw? It's not a flaw, but a design choice that gives developers the freedom to choose their level of formality. The "inconsistency" is that you can write code with or without types.

Conclusion: Inconsistency as a Design Philosophy

When you look at these examples, a pattern emerges. Python's "inconsistencies" are often the result of prioritizing:

- Readability and "Pythonic" Style: Code should be easy for humans to read.

snake_caseis often more readable thancamelCase. - Practicality over Purity: The mutable default argument is a perfect example. It's a "gotcha," but changing it would be impractical. The solution is to learn the common idiom.

- "There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it." Often, the "inconsistency" comes from there being multiple valid ways to do something, and the community has settled on a "most obvious" one (e.g., using

Nonefor mutable defaults). - Pragmatism: Integrating with existing C libraries (like

Tkinter) meant adopting their naming conventions.

So, is Python inconsistent? Yes, in some specific, often historical or pragmatic, ways.

But is it badly designed? Most developers would say no. These quirks are a trade-off for the language's greatest strengths: its incredible readability, its vast ecosystem, and its "batteries-included" philosophy that gets you from idea to working code faster than almost anything else. The key is to learn these patterns and embrace the "Pythonic" way of thinking.