Of course! This is a very common point of confusion in Java because of the evolution of its date and time APIs. Let's break it down clearly.

The Core Concept: Timestamp vs. Date

First, it's crucial to understand the difference in a general sense:

- Timestamp: Represents a single, specific instant on the timeline. It's a point in time, precise to the nanosecond. It's independent of any particular time zone or calendar system. Think of it as a raw number of ticks since a fixed point in the past (the "epoch").

- Date: Represents a date and time, but it's almost always tied to a specific time zone and calendar system (like the Gregorian calendar). It's a human-readable representation of a point in time.

The Old Way: java.util.Date and java.sql.Timestamp

These are the legacy classes, mostly from Java 1.1. You will still encounter them, especially in older codebases or when interacting with databases.

java.util.Date

This class was designed to represent both a date and a time. However, it has a major design flaw: it internally stores the time as a long millisecond value since the Unix epoch (January 1, 1970, 00:00:00 UTC), but its getter methods (like getHours(), getMinutes()) were deprecated because they operate on the local time zone of the system where the code is running. This creates ambiguity and makes it unreliable.

Key Points:

- Stores: A single point in time (milliseconds since epoch).

- Problem: Its methods for accessing date/time components are tied to the local system's default time zone, which is a source of bugs.

- Best Practice: Treat

java.util.Dateas a simple container for a millisecond value. Avoid its deprecated methods.

java.sql.Timestamp

This class is a thin wrapper around java.util.Date. It was created specifically for JDBC to interact with SQL TIMESTAMP types. It adds the ability to store nanoseconds.

Key Points:

- Extends:

java.util.Date. - Stores: Milliseconds and nanoseconds since the epoch.

- Use Case: Primarily for database operations. You should avoid using it for general application logic.

The Modern Way: java.time (Java 8+)

Since Java 8, the official and recommended way to handle dates and times is with the java.time package. It's more powerful, immutable, and thread-safe. The key classes here are Instant, LocalDateTime, and ZonedDateTime.

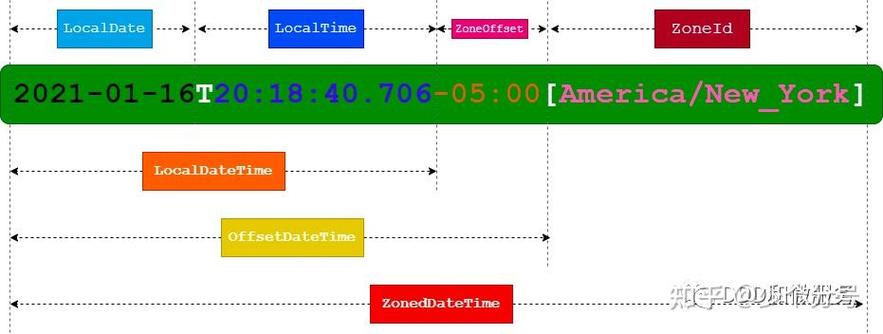

java.time.Instant

This is the modern equivalent of a timestamp. It represents a specific moment on the timeline, independent of a time zone, measured in seconds and nanoseconds from the Unix epoch.

Key Points:

- Represents: A point in time (UTC).

- Analogy: A raw timestamp, like a system clock reading.

- Perfect for: Storing in a database, logging events, or representing a point in time that doesn't need to be displayed to a user in a specific zone.

import java.time.Instant;

// Get the current moment from the system clock in UTC

Instant now = Instant.now();

System.out.println("Current Instant: " + now);

// Get the epoch seconds (seconds since 1970-01-01T00:00:00Z)

long epochSecond = now.getEpochSecond();

System.out.println("Epoch Second: " + epochSecond);

// Get the nanoseconds of the second

int nano = now.getNano();

System.out.println("Nanosecond of second: " + nano);

java.time.LocalDateTime

This class represents a date and time, but without any time zone information. It's useful for representing events that happen in a "local" context, like a meeting scheduled for "2025-10-27T10:15:30" without specifying if that's in New York or Tokyo.

Key Points:

- Represents: A date-time without a time zone (e.g., "the 27th of October at 10:15:30").

- Analogy: A local appointment on a calendar.

- Caution: Because it has no time zone, you cannot convert it to an

Instantor anotherZonedDateTimewithout specifying a time zone. This can lead to errors if you're not careful.

import java.time.LocalDateTime;

// Get the current date and time from the system's clock in the default time zone

LocalDateTime now = LocalDateTime.now();

System.out.println("Current LocalDateTime: " + now);

// Create a specific LocalDateTime

LocalDateTime meeting = LocalDateTime.of(2025, 10, 27, 10, 30);

System.out.println("Meeting time: " + meeting);

java.time.ZonedDateTime

This class represents a date and time with a specific time zone. This is the most complete representation for human-centric events. It tells you exactly what time it is and where that time is being measured.

Key Points:

- Represents: A date-time with a time zone (e.g., "2025-10-27T10:15:30+02:00[Europe/Paris]").

- Analogy: A scheduled flight: "Flight departs at 10:30 AM Paris Time."

- Best For: Scheduling, user-facing displays, and any application where the location of the time is important.

import java.time.ZonedDateTime;

import java.time.ZoneId;

// Get the current date and time in a specific time zone

ZonedDateTime nowInParis = ZonedDateTime.now(ZoneId.of("Europe/Paris"));

System.out.println("Now in Paris: " + nowInParis);

// Create a specific ZonedDateTime

ZonedDateTime flightDeparture = ZonedDateTime.of(2025, 10, 27, 10, 30, 0, 0, ZoneId.of("America/New_York"));

System.out.println("Flight departure in NYC: " + flightDeparture);

Conversion Cheat Sheet

Here’s how you move between these modern types:

| From | To | How |

|---|---|---|

Instant |

ZonedDateTime |

instant.atZone(zoneId) |

ZonedDateTime |

Instant |

zonedDateTime.toInstant() |

LocalDateTime |

ZonedDateTime |

localDateTime.atZone(zoneId) |

ZonedDateTime |

LocalDateTime |

zonedDateTime.toLocalDateTime() |

Instant |

LocalDateTime |

instant.atZone(zoneId).toLocalDateTime() |

LocalDateTime |

Instant |

localDateTime.atZone(zoneId).toInstant() |

Legacy to Modern Conversion

You often need to convert between the old java.util.* classes and the new java.time classes.

java.util.Date ↔ java.time.Instant

This is the most common conversion. Since java.util.Date is just a millisecond value, it maps directly to Instant.

import java.util.Date; import java.time.Instant; // Old to New Date oldDate = new Date(); Instant instant = oldDate.toInstant(); // Easy! // New to Old Instant newInstant = Instant.now(); Date newDate = Date.from(newInstant); // Also easy!

java.sql.Timestamp ↔ java.time.Instant

The conversion is similar, but Timestamp has nanosecond precision.

import java.sql.Timestamp; import java.time.Instant; // Old to New Timestamp oldTimestamp = new Timestamp(System.currentTimeMillis()); Instant instant = oldTimestamp.toInstant(); // New to Old Instant newInstant = Instant.now(); Timestamp newTimestamp = Timestamp.from(newInstant);

java.util.Date ↔ java.time.LocalDateTime

This is more complex because Date is UTC-based and LocalDateTime is not.

import java.util.Date; import java.time.LocalDateTime; import java.time.ZoneId; // Old to New Date oldDate = new Date(); LocalDateTime localDateTime = oldDate.toInstant().atZone(ZoneId.systemDefault()).toLocalDateTime(); // New to Old LocalDateTime newLocalDateTime = LocalDateTime.now(); Date newDate = Date.from(newLocalDateTime.atZone(ZoneId.systemDefault()).toInstant());

Summary and Best Practices

| Class | What It Represents | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

java.util.Date |

A point in time (ms since epoch), with flawed methods. | Avoid in new code. Use only for interop with legacy systems. |

java.sql.Timestamp |

A JDBC-specific timestamp with nanoseconds. | Only for database operations. Avoid in application logic. |

java.time.Instant |

A point in time, UTC-based, high precision. | Your go-to for timestamps. Storing events, logging, database storage. |

java.time.LocalDateTime |

A date-time, no time zone. | Modeling local events (e.g., "a store's opening time"). Be cautious with conversions. |

java.time.ZonedDateTime |

A date-time with a time zone. | **The best choice for user-facing |