Of course! Let's break down how to make HTTP GET requests in Python, starting with the older urllib2 and then showing the modern, recommended way using the requests library.

The Modern and Recommended Way: requests Library

First and foremost, for any new project, you should use the requests library. It's designed to be more user-friendly, powerful, and Pythonic than the built-in modules.

Installation

If you don't have it installed, open your terminal or command prompt and run:

pip install requests

Simple GET Request Example

This is the most common use case: fetching the content of a webpage.

import requests

# The URL you want to get data from

url = 'https://www.example.com'

try:

# Send a GET request to the URL

response = requests.get(url)

# Raise an exception if the request was unsuccessful (e.g., 404 Not Found, 500 Server Error)

response.raise_for_status()

# The content of the response, decoded automatically from bytes to a string

# .text is for text-based content (HTML, JSON, etc.)

html_content = response.text

# Print the first 500 characters of the HTML

print("Successfully fetched the page!")

print(f"Status Code: {response.status_code}")

print(f"Content-Type: {response.headers['Content-Type']}")

print("-" * 20)

print(html_content[:500])

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

# Handle any errors that occur during the request (e.g., connection error, timeout)

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

Key requests Features:

- Simplicity:

requests.get(url)is all you need for a basic GET request. - Automatic Decoding: It automatically decodes the response content (e.g., from gzip) into a string using the correct encoding.

- JSON Handling:

response.json()is a convenient method to parse JSON responses directly into a Python dictionary. - Easy Access to Headers & Status:

response.headers,response.status_code,response.urlare easy to access. - Session Objects:

requests.Session()allows you to persist parameters across requests, which is great for cookies and authentication.

The Older Way: urllib2 (and urllib in Python 3)

urllib2 was the standard library module in Python 2. In Python 3, it was split and merged into urllib.request and urllib.error. You should generally avoid this for new code, but it's useful to know for maintaining older Python 2 scripts or for environments where you cannot install external libraries.

Python 3: urllib.request

Here is the equivalent GET request using Python 3's built-in urllib.request.

import urllib.request

import urllib.error

# The URL you want to get data from

url = 'https://www.example.com'

try:

# Create a request object

# You can add headers here, e.g., req = urllib.request.Request(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'MyApp/1.0'})

req = urllib.request.Request(url)

# Open the URL and get a response object

# This is a context manager (with statement) which is good practice

with urllib.request.urlopen(req) as response:

# The response data is in bytes, so you need to decode it to a string

# response.read() returns the entire content as bytes

html_bytes = response.read()

# Get the encoding from the headers, default to 'utf-8' if not found

encoding = response.headers.get_content_charset()

if encoding is None:

encoding = 'utf-8'

html_content = html_bytes.decode(encoding)

# Print the first 500 characters of the HTML

print("Successfully fetched the page!")

print(f"Status Code: {response.status}") # Note: it's .status, not .status_code

print(f"Content-Type: {response.headers.get('Content-Type')}")

print("-" * 20)

print(html_content[:500]

except urllib.error.URLError as e:

# Handle URL errors (e.g., 404, 500)

print(f"An error occurred: {e.reason}")

except Exception as e:

# Handle other potential errors

print(f"An unexpected error occurred: {e}")

Python 2: urllib2

If you are working with a legacy Python 2 codebase, the syntax is slightly different.

# Python 2

import urllib2

import urllib

url = 'https://www.example.com'

try:

# Create a request object

req = urllib2.Request(url)

# Open the URL and get a response object

response = urllib2.urlopen(req)

# The response data is in bytes

html_bytes = response.read()

# Decode to a string

html_content = html_bytes.decode('utf-8') # Or the correct encoding

# Print the first 500 characters

print("Successfully fetched the page!")

print(f"Status Code: {response.code}") # Note: it's .code

print(f"Content-Type: {response.headers.getheader('Content-Type')}")

print("-" * 20)

print(html_content[:500]

except urllib2.URLError as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e.reason}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An unexpected error occurred: {e}")

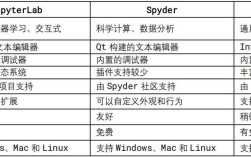

Comparison: requests vs. urllib.request

| Feature | requests (Recommended) |

urllib.request (Built-in) |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of Use | Excellent. Very intuitive and Pythonic. | Fair. More verbose and less intuitive. |

| Installation | Requires pip install requests. |

Built-in, no installation needed. |

| JSON Handling | response.json() automatically parses JSON. |

Manual parsing required using json.loads(). |

| URL Encoding | requests handles it automatically. |

Manual handling required (urllib.parse.quote). |

| Sessions/Cookies | Easy with requests.Session(). |

Possible but more complex. |

| Response Object | response.text (string), response.content (bytes). |

response.read() (bytes), manual decoding needed. |

| Error Handling | response.raise_for_status() and specific exception classes. |

try...except urllib.error.URLError. |

Conclusion

| When to Use | Why |

|---|---|

requests |

Almost always. For any new project, personal script, or professional development. It saves time and reduces boilerplate code. |

urllib.request |

When you cannot install third-party libraries (e.g., in some restricted environments or coding challenges that forbid it). |

For learning and modern Python development, start with requests. It will make your life much easier. Use urllib.request only when you have a specific reason to avoid external dependencies.