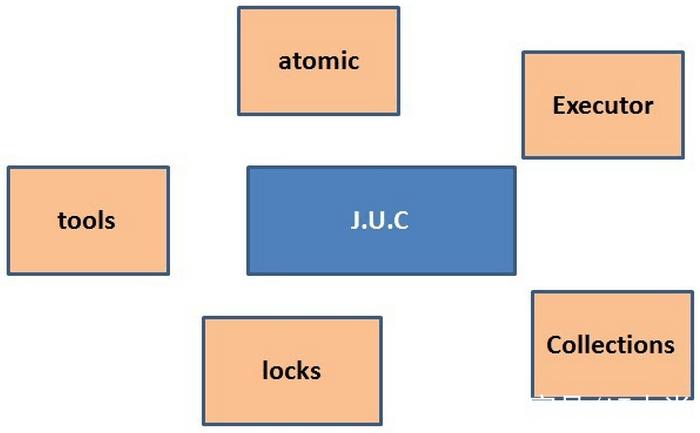

Of course! The java.util.concurrent package, often abbreviated as JUC, is a cornerstone of modern Java development. It was introduced in Java 5 to address the complexities of multithreading and concurrency, providing high-performance, robust, and easy-to-use alternatives to the low-level synchronized keyword and the java.util.concurrent.atomic package.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of java.util.concurrent, covering its importance, key components, and best practices.

Why is java.util.concurrent So Important?

Before Java 5, concurrent programming was difficult and error-prone. Developers had to rely on:

- The

synchronizedkeyword, which is powerful but can lead to deadlocks, starvation, and performance bottlenecks if not used carefully. java.lang.Thread, which gave direct control over threads but made managing a pool of threads for tasks very difficult.java.util.concurrent.atomicfor lock-free programming, but it was limited to single variables.

The JUC package solved these problems by providing:

- High-Performance Primitives: Tools like

ConcurrentHashMapandCopyOnWriteArrayListare significantly faster than their synchronized counterparts under high contention. - Scalability: Many components are designed to scale well with the number of CPU cores.

- Simplified Thread Management: The

Executorframework abstracts away the manual creation and management of threads. - Powerful Synchronization Utilities: Tools like

CountDownLatch,CyclicBarrier, andSemaphoremake complex coordination between threads much simpler. - Thread-Safe Data Structures: Collections that are safe to use by multiple threads without external synchronization.

Core Components of java.util.concurrent

The package is vast, but we can break it down into logical categories.

A. The Executor Framework (The Heart of Concurrency)

This is the most important part to understand. It provides an abstraction for executing Runnable or Callable tasks asynchronously. Instead of creating a new thread for every task, you submit tasks to an Executor, which manages a pool of reusable threads.

Key Interfaces and Classes:

Executor(Interface): The simplest interface, with a single methodexecute(Runnable command). It's a very basic abstraction.ExecutorService(Interface): A more useful sub-interface. It manages a lifecycle (shutdown(),shutdownNow()) and provides methods to submit tasks that return aFuture(submit()).ThreadPoolExecutor(Class): The full-featured, highly configurable implementation ofExecutorService. You can control the core pool size, maximum pool size, keep-alive time, and the work queue.Executors(Utility Class): A factory class for creating pre-configuredExecutorServiceinstances. This is the easiest way to get started.

Common Executors Factory Methods:

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(int nThreads): Creates a thread pool with a fixed number of threads. Tasks are queued if all threads are busy.Executors.newCachedThreadPool(): Creates a thread pool that can grow as needed. It's good for many short-lived tasks. Threads that are idle for 60 seconds are terminated.Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor(): Creates a single-threaded executor. All tasks are executed sequentially, which is useful for ensuring tasks are executed in a specific order.

Example: Using ExecutorService

import java.util.concurrent.*;

public class ExecutorExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a thread pool with 2 threads

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(2);

// Submit tasks to the executor

executor.submit(() -> {

System.out.println("Task 1 running in thread: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

try { Thread.sleep(1000); } catch (InterruptedException e) {}

System.out.println("Task 1 finished.");

});

executor.submit(() -> {

System.out.println("Task 2 running in thread: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

try { Thread.sleep(500); } catch (InterruptedException e) {}

System.out.println("Task 2 finished.");

});

// Shut down the executor. No new tasks will be accepted.

executor.shutdown();

}

}

B. Thread-Safe Collections

These data structures are designed to be used by multiple threads without requiring external synchronized blocks.

| Collection | Key Feature | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

ConcurrentHashMap |

Highly scalable. Uses fine-grained locking (lock striping) to allow concurrent reads and different segments of the map to be written simultaneously. | The default choice for a thread-safe Map. Replaces Hashtable and Collections.synchronizedMap(new HashMap<>()). |

CopyOnWriteArrayList |

Any modification (add, set, remove) creates a fresh copy of the underlying array. Reads are lock-free and extremely fast. | Read-heavy lists with very few modifications. Excellent for event listeners (Observable pattern). |

ConcurrentLinkedQueue |

A non-blocking, thread-safe queue based on linked nodes. Uses CAS (Compare-And-Swap) operations. |

High-throughput, non-blocking queue where order of processing is FIFO. |

ConcurrentSkipListMap |

A concurrent, scalable NavigableMap implementation based on a SkipList. Provides ordered functionality. |

A concurrent alternative to TreeMap or Collections.synchronizedSortedMap. |

C. Synchronizers

These are utilities that allow threads to wait for each other to reach a common point of execution.

-

CountDownLatch: A one-off barrier. One or more threads can wait for a set of operations, performed by other threads, to complete.- Use Case: Waiting for several initialization threads to finish before starting the main application thread.

-

CyclicBarrier: A reusable barrier. Threads wait for each other to reach a common barrier point. When the specified number of threads arrive, the barrier is "tripped" and all threads are released.- Use Case: Parallel processing where you need to wait for all parallel tasks to finish before aggregating the results (e.g., in a map-reduce pattern).

-

Semaphore: A counting semaphore. It maintains a set of permits. Threads canacquire()a permit (blocking if none are available) andrelease()it when done.- Use Case: Limiting the number of threads that can access a resource (e.g., a database connection pool, a file system).

D. Low-Level Concurrency Primitives

These are the building blocks for creating your own custom concurrency classes.

Atomicclasses (AtomicInteger,AtomicLong,AtomicReference, etc.): Provide lock-free, thread-safe operations on single variables usingCAS(Compare-And-Swap) instructions. Much faster thansynchronizedblocks for simple increment/decrement operations.LockInterface: An alternative tosynchronizedblocks. The main implementation isReentrantLock.- Advantages over

synchronized: It can belock()ed andunlock()ed in different methods (unlikesynchronizedblocks which must be in the same scope). It supports non-blocking tries (tryLock()) and interruptible lock acquisition (lockInterruptibly()).

- Advantages over

ReadWriteLockInterface: Allows for greater concurrency by separating "read" and "write" locks. Multiple threads can hold a read lock simultaneously, but only one thread can hold a write lock (and no other threads can hold any lock).- Use Case: Data structures that are read far more often than they are written (e.g., a configuration cache).

E. Future and CompletableFuture

-

Future<V>(Interface): Represents the result of an asynchronous computation. AFutureprovides methods to check if the computation is complete, to wait for its completion, and to retrieve the result.- Problem:

get()is a blocking call, which can defeat the purpose of asynchronous programming.

- Problem:

-

CompletableFuture<T>(Class): The modern, non-blocking future introduced in Java 8. It's the cornerstone of asynchronous programming in Java.- Key Features:

- Composition: You can chain operations using

thenApply(),thenAccept(),thenCompose(), etc. - Non-blocking: It uses a callback model, so your code doesn't block while waiting for a result.

- Exception Handling: Provides

exceptionally()andhandle()for clean error propagation. - Combining: You can combine multiple

CompletableFuturesusingthenCombine(),allOf(),anyOf().

- Composition: You can chain operations using

- Key Features:

Best Practices

- Prefer

ExecutorServiceover rawThread: Always use the executor framework. It manages thread lifecycle, resource usage, and provides a clean way to get results. - Choose the Right Data Structure: Don't use

Collections.synchronizedMap()orVectorwhenConcurrentHashMapis available. The performance difference is