Of course! This is a fantastic question because it gets to the heart of how the web works. Let's break down the relationship between Python's http and socket modules, from the simple, high-level way to the low-level, fundamental way.

The Core Analogy: A Phone Call

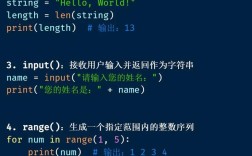

Think of it like making a phone call:

-

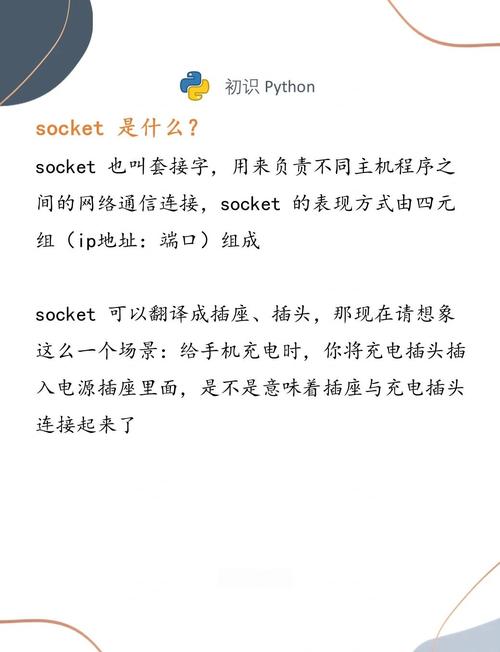

socketis the Telephone Network: It's the fundamental, low-level infrastructure. It lets you establish a connection (pick up the phone), send raw data (speak words), and receive raw data (listen for words). It doesn't care if you're having a conversation, ordering a pizza, or just listening to a dial tone. It just handles the connection and the data stream. -

httpis the Language and Rules of Conversation: HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is a set of rules for what you say and when you say it. When you call a restaurant, you don't just shout "PIZZA!". You follow a protocol: "Hello, may I please order a pizza?" The restaurant understands this request and responds with a set of rules ("What kind?"). HTTP does the same for web data, defining request methods (GET, POST), headers, and status codes (200 OK, 404 Not Found).

In short: http is built on top of socket. The http library uses socket in the background to do the actual communication, but it handles all the complex formatting of the HTTP protocol for you.

The High-Level Way: Using the http.client Module (Recommended)

For almost all web-related tasks in Python, you should use the built-in http.client module (or its more user-friendly third-party cousin, the requests library). It's easy, powerful, and abstracts away all the socket-level details.

This module is perfect for making HTTP requests to a web server.

Example: Making a GET Request

Let's fetch the content of http://example.com.

import http.client

import ssl

# The host and the port

host = "example.com"

port = 443 # Use 443 for HTTPS, 80 for HTTP

# We create a connection object. For HTTPS, we need to wrap it in an SSL context.

# http.client will handle the HTTP protocol formatting for us.

try:

# For HTTPS

context = ssl.create_default_context()

conn = http.client.HTTPSConnection(host, port, context=context)

# For HTTP (uncomment to use)

# conn = http.client.HTTPConnection(host, port)

# We send a GET request for the root path "/"

print(f"Sending GET request to {host}")

conn.request("GET", "/")

# Get the response from the server

response = conn.getresponse()

# Check if the request was successful

if response.status == 200:

print(f"Status: {response.status} {response.reason}")

print("Headers:", response.getheaders())

# Read the response data (the HTML content)

data = response.read()

print("\n--- Response Data (first 200 bytes) ---")

print(data[:200].decode('utf-8'))

else:

print(f"Error: {response.status} {response.reason}")

# Always close the connection

conn.close()

except ConnectionRefusedError:

print(f"Connection to {host}:{port} was refused.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

What this code does:

HTTPSConnection: Creates a secure socket connection toexample.comon port 443. It handles the SSL/TLS handshake for you.conn.request("GET", "/"): This is the magic part. It doesn't just send "/". It formats a complete, valid HTTP request:GET / HTTP/1.1 Host: example.com User-Agent: Python-urllib/3.11 Accept-Encoding: identity Connection: closeconn.getresponse(): Receives the server's raw response, including the status line, headers, and the body.response.read(): Reads the body of the response.

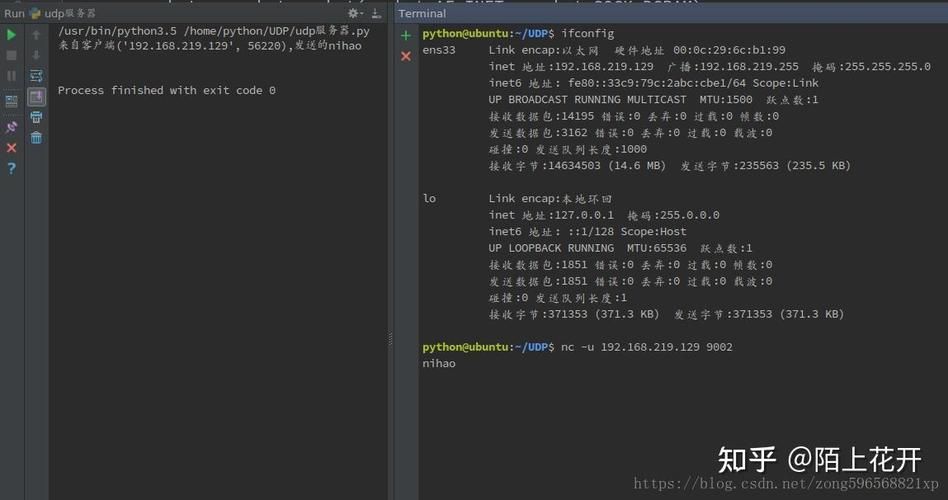

The Low-Level Way: Using the socket Module

This is how you would build a simple HTTP client from scratch. It's great for understanding the fundamentals but is much more verbose and error-prone. You are responsible for every single byte of the HTTP request and response.

We will create a simple HTTP client that fetches http://example.com.

import socket

HOST = "example.com"

PORT = 80 # HTTP uses port 80

# 1. Create a socket object (IPv4, TCP)

# AF_INET -> IPv4 address family

# SOCK_STREAM -> TCP socket type

client_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

try:

# 2. Connect to the server

print(f"Connecting to {HOST}:{PORT}...")

client_socket.connect((HOST, PORT))

# 3. Prepare the HTTP request as a byte string

# Note the \r\n line endings required by the HTTP protocol

request = f"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: {HOST}\r\nConnection: close\r\n\r\n"

print(f"\nSending request:\n{request}")

# 4. Send the request to the server

# encode() converts the string to bytes

client_socket.sendall(request.encode('utf-8'))

# 5. Receive the response from the server

# We'll read data in chunks until there's nothing left

print("\nReceiving response...")

response = b""

while True:

chunk = client_socket.recv(4096) # Read up to 4096 bytes

if not chunk:

break

response += chunk

# 6. Process the response

print("--- Full Response ---")

# decode() converts the bytes back to a string for printing

print(response.decode('utf-8'))

except ConnectionRefusedError:

print(f"Connection to {HOST}:{PORT} was refused.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

finally:

# 7. Close the socket connection

print("\nClosing connection.")

client_socket.close()

What this code does:

socket.socket(...): Creates a raw TCP socket.client_socket.connect(...): Establishes the underlying connection.request = ...: You manually create the entire HTTP request string. You must get the format, headers, and line endings (\r\n) exactly right.client_socket.sendall(...): Sends your raw bytes to the server. No formatting help is given.client_socket.recv(...): Receives raw bytes back from the server. You get the entire HTTP response: status line, headers, and body, all jumbled together.response.decode(...): You are responsible for parsing this raw text to find the status code, headers, and body. It's a lot of work!

Building a Simple HTTP Server with socket

To see the other side of the coin, let's build a very basic HTTP server using socket. This server will only ever respond with a fixed "Hello, World!" message.

import socket

HOST = "127.0.0.1" # Standard loopback interface address (localhost)

PORT = 65432 # Port to listen on (non-privileged ports are > 1023)

# Create a socket object

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

# Set an option to allow the address to be reused immediately

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

# Bind the socket to the address and port

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

# Listen for incoming connections (queue up to 5)

s.listen()

print(f"Server listening on {HOST}:{PORT}")

# Accept a connection

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

# Receive data from the client (up to 1024 bytes)

data = conn.recv(1024)

print(f"Received from client:\n{data.decode('utf-8')}")

# Our simple HTTP response

# Note the double \r\n\r\n to signal the end of headers

response_body = "Hello, World from our Python Socket Server!"

response = (

"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\n"

"Content-Type: text/plain\r\n"

f"Content-Length: {len(response_body)}\r\n"

"Connection: close\r\n"

"\r\n"

f"{response_body}"

)

# Send the response back to the client

conn.sendall(response.encode('utf-8'))

print("Response sent.")

How to test this server:

- Save the code as

server.py. - Run it from your terminal:

python server.py. You'll see "Server listening on 127.0.0.1:65432". - Open a new terminal and use a command-line tool like

curl:curl http://127.0.0.1:65432

- You will see the output:

Hello, World from our Python Socket Server! - Look back at your server terminal; you'll see the raw HTTP request from

curland the "Response sent." message.

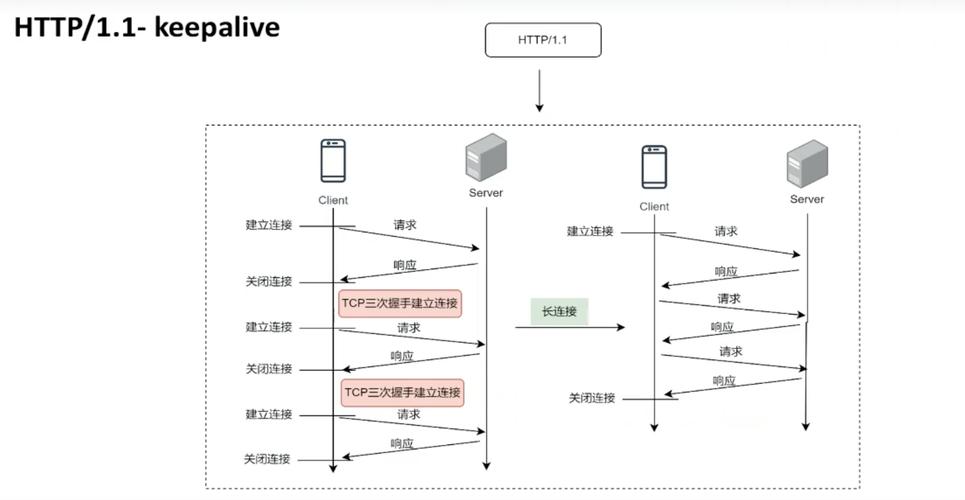

Summary: When to Use Which

| Feature | http.client / requests |

socket |

|---|---|---|

| Abstraction Level | High-Level | Low-Level |

| Purpose | Interacting with web servers (HTTP/HTTPS). | General-purpose network communication (TCP, UDP). |

| Ease of Use | Very easy. Handles headers, encoding, SSL, etc. | Complex. You must implement protocols manually. |

| Use Case | Fetching web pages, calling REST APIs, web scraping. | Building custom protocols, game servers, chat apps, or learning about networking. |

| Recommendation | Use this 99% of the time for web-related tasks. | Use this when you need to go beyond HTTP or want to understand the fundamentals. |