Of course. "Thinking in Python" is a fantastic concept. It's not just about knowing the syntax; it's about adopting a specific mindset, a way of approaching problems that is idiomatic, efficient, and powerful.

Let's break down what it means to "think in Python," moving from core principles to practical techniques.

Part 1: The Foundational Mindset

This is the philosophical shift from other languages (especially C++ or Java) to Python.

"There Should Be One—And Preferably Only One—Obvious Way to Do It." (The Zen of Python)

This principle, often called the "Pythonic" way, encourages clarity and simplicity. When you write code, ask yourself: "Is this the most straightforward, readable way to express this idea?" If not, there's probably a more Pythonic way.

Readability Counts

Code is read far more often than it is written. Python's emphasis on clean, readable syntax (using indentation, not braces) is a core feature. A Pythonista strives to make their code self-documenting.

- Bad:

x = [y for y in my_list if y > 0] - Good:

positive_numbers = [y for y in my_list if y > 0]

The variable name positive_numbers tells you exactly what the list contains, making the code much easier to understand.

"Explicit is better than implicit."

Don't make the reader (or the interpreter) guess. Be clear about what you're doing.

- Less Pythonic (Implicit):

f = open('file.txt'); print(f.read()); f.close()(What if an error occurs afteropenbut beforeclose?) - More Pythonic (Explicit): The

withstatement handles this perfectly.with open('file.txt') as f: print(f.read())Here, it's explicitly clear that the file will be closed automatically when the

withblock is exited, even if errors occur.

Part 2: Core Pythonic Idioms

These are the building blocks of Pythonic thinking.

Embrace Everything is an Object

In Python, everything—integers, lists, functions, classes—is an object. This means:

- You can pass functions as arguments to other functions.

- You can assign functions to variables.

- Objects have attributes (data) and methods (functions that belong to the object).

my_string = "hello"

print(type(my_string)) # <class 'str'>

print(my_string.upper()) # HELLO

# Functions are objects too!

def greet(name):

return f"Hello, {name}"

greeting_func = greet

print(greeting_func("Alice")) # Hello, Alice

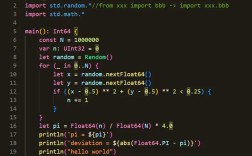

Leverage Dynamic Typing (with Responsibility)

Python doesn't require you to declare variable types. This makes for fast and flexible prototyping. The responsibility is on the programmer to ensure the right types are used where they are expected.

# This is perfectly valid in Python my_variable = 10 print(my_variable) my_variable = "Now I'm a string" print(my_variable)

Modern Python uses type hints (my_variable: int = 10) to help catch errors and improve code documentation, but the core language remains dynamically typed.

Use "Easier to Ask for Forgiveness than Permission" (EAFP)

This is a cornerstone of Pythonic error handling. Instead of checking if an operation is possible before you try it (LBYL - Look Before You Leap), just try it and handle the potential exception.

-

LBYL (Less Pythonic):

if key in my_dict: value = my_dict[key] else: value = "default" -

EAFP (More Pythonic):

try: value = my_dict[key] except KeyError: value = "default"This is often considered more readable and performant, as checking for existence (

in) can be as expensive as thedictlookup itself.

Part 3: Mastering Python's "Power Tools"

This is where you start writing truly expressive and efficient code.

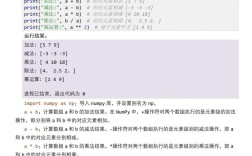

List/Dict/Set Comprehensions

This is the single most important feature for writing clean, concise, and fast code. Comprehensions are a compact way to create lists, dictionaries, or sets based on existing iterables.

-

The Problem: Create a list of squares for numbers 1 to 10.

-

The Imperative Way (Verbose):

squares = [] for i in range(1, 11): squares.append(i * i) -

The Pythonic Way (Comprehension):

squares = [i * i for i in range(1, 11)]

You can even add conditions:

# Get squares of only the even numbers even_squares = [i * i for i in range(1, 11) if i % 2 == 0]

Comprehensions for dictionaries and sets work similarly:

# Create a dictionary mapping number to its square

square_map = {i: i * i for i in range(1, 11)}

# Create a set of unique letters

unique_letters = {letter for letter in "abracadabra"}

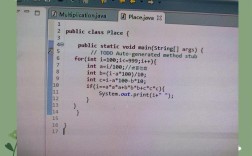

Iterate Like a Pro: for, enumerate, zip, itertools

Don't just use for item in my_list:. Use the right tool for the job.

-

enumerate: When you need both the index and the item.# Not Pythonic for i in range(len(my_list)): print(f"Index {i}: {my_list[i]}") # Pythonic for index, item in enumerate(my_list): print(f"Index {index}: {item}") -

zip: To iterate over multiple iterables in parallel.names = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'] ages = [30, 25, 35] for name, age in zip(names, ages): print(f"{name} is {age} years old.") -

itertools: The ultimate toolbox for advanced iteration. It's lazy, meaning it doesn't compute values until it needs to, making it incredibly memory-efficient.import itertools # Cycle through a list forever counter = itertools.cycle(['A', 'B', 'C']) print(next(counter)) # A print(next(counter)) # B print(next(counter)) # C print(next(counter)) # A # Get only the first 5 items from an infinite generator first_five = itertools.islice(itertools.count(10), 5) print(list(first_five)) # [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Use Context Managers (with statement)

We saw this earlier, but it's so important it's worth re-emphasizing. Use with for anything that needs to be set up and torn down: files, database connections, network sockets, etc. It guarantees cleanup happens.

# Database connection example

with db.connect('my_database') as connection:

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM users")

users = cursor.fetchall()

# The connection is automatically closed here

Part 4: Thinking in Functions and Data

Prefer Built-in Functions and Libraries

Python's standard library is vast and powerful. Before you write a function to do something, check if it already exists.

- Don't write your own

maxfunction. Usemax(). - Don't write your own sorting algorithm. Use

my_list.sort()orsorted(my_list). - Don't reinvent the wheel. Need to work with JSON? Use

json. Need to make HTTP requests? Userequests. Need to parse dates? Usedatetime.

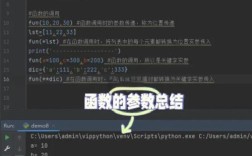

Write Small, Focused Functions

A function should do one thing and do it well. This makes your code easier to test, debug, and reuse.

- Bad: A function that fetches data from an API, parses it, formats it into a report, and emails it.

- Good:

fetch_data_from_api(url)parse_json_response(json_string)format_data_as_report(data)send_email(recipient, subject, body)- A main function that orchestrates these calls.

Embrace Duck Typing

"If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck."

Instead of checking an object's type, just try to use it as if it were the type you expect. If it has the method you need, great! If not, it will raise an appropriate error.

def calculate_length(item):

# We don't care if it's a list, a string, a tuple, etc.

# We just care if it has a __len__ method.

return len(item)

print(calculate_length([1, 2, 3])) # 3

print(calculate_length("hello")) # 5

print(calculate_length({"a": 1})) # 1 (number of keys)

Part 5: The Path to Mastery

- Read Good Code: Go on GitHub and read the source code of popular libraries like

requests,Flask, orpandas. See how the masters solve problems. - Use an Linter: Tools like

PylintandFlake8will flag non-Pythonic code and style issues. Listen to them. - Embrace Testing: Write unit tests for your functions. This forces you to write small, testable, and well-defined code.

- Refactor: Don't try to write the perfect Pythonic function on the first try. Write something that works, then go back and refactor it to be cleaner and more expressive.

By internalizing these principles and idioms, you'll move from writing code that runs in Python to writing code that thinks in Python.