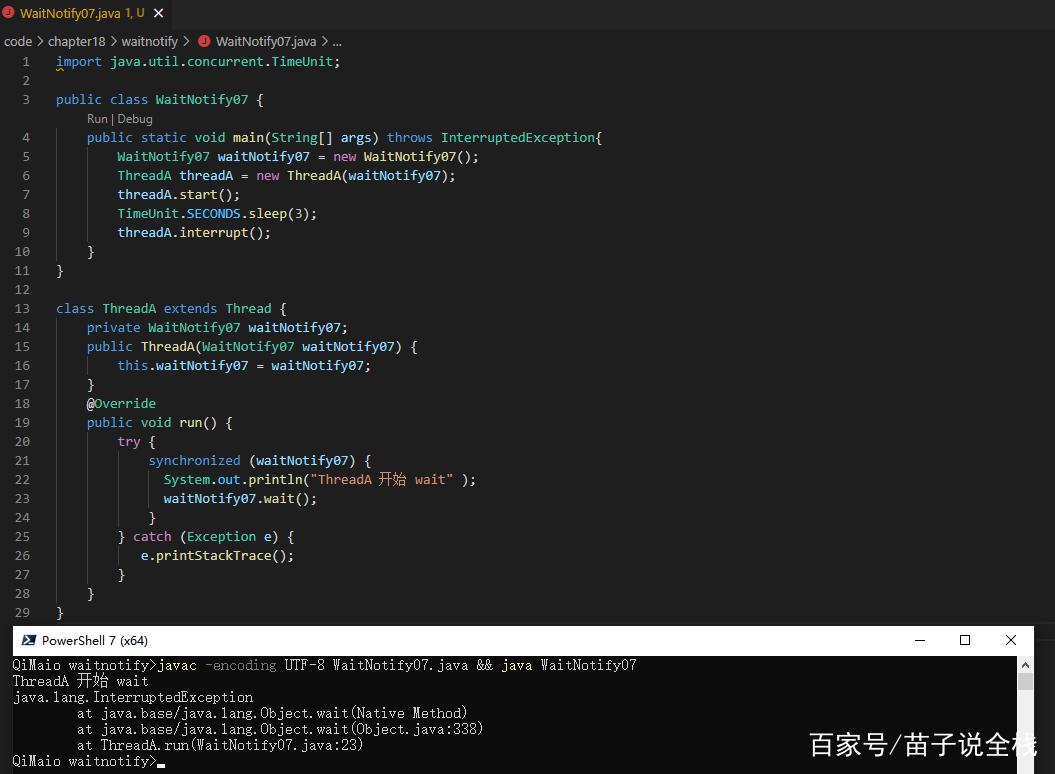

Of course! Let's break down notify() and wait() in Java. They are fundamental tools for writing multi-threaded applications, but they are often misunderstood and misused.

The Core Concept: Thread Communication

Imagine you have two threads: a Producer and a Consumer.

- The Producer creates data and puts it into a shared buffer.

- The Consumer takes data from the shared buffer to process it.

What happens if the buffer is empty? The Consumer can't do anything. It should wait until the Producer adds data. What happens if the buffer is full? The Producer can't add more data. It should wait until the Consumer takes some data away.

wait() and notify() are the mechanisms that allow these threads to communicate with each other and coordinate their actions efficiently, without wasting CPU cycles.

The Golden Rule: Always Use synchronized

wait() and notify() are not magic methods. They must be called from within a synchronized block or method. This is crucial for two reasons:

- Mutual Exclusion: It ensures that only one thread can manipulate the shared resource (the buffer) at a time, preventing race conditions.

- Memory Visibility: It guarantees that changes made to shared variables by one thread are visible to other threads when they acquire the same lock.

The wait() Method

When a thread calls wait() on an object, it does the following:

- It releases the lock it holds on that object.

- It enters the wait set of that object.

- It suspends execution and waits until one of three things happens:

- Another thread calls

notify()ornotifyAll()on the same object. - Another thread calls

interrupt()on the waiting thread. - The specified waiting time (if you use

wait(long timeout)) has elapsed.

- Another thread calls

Key takeaway: wait() releases the lock, allowing other threads to enter the synchronized block and potentially call notify().

The notify() Method

When a thread calls notify() on an object, it does the following:

- It wakes up one (arbitrarily chosen) thread from the wait set of that object.

- The awakened thread then attempts to re-acquire the lock on the object. It will block until the current thread (the one that called

notify) releases the lock.

Key takeaway: notify() wakes up one waiting thread. It does not release the lock immediately. The lock is released when the synchronized block/method exits.

notifyAll() vs. notify()

notify(): Wakes up one random thread from the wait set. Use this when you know that any of the waiting threads can proceed and you want to minimize context switching.notifyAll(): Wakes up all threads waiting on that object. All awakened threads will then compete to re-acquire the lock. Only one will succeed; the others will go back to waiting. Use this when you don't know which thread should proceed or when a condition change is relevant to all waiting threads.

The Classic Example: Producer-Consumer

This is the best way to understand how they work together.

The Shared Resource (Buffer)

This class will hold the data and the synchronized methods.

public class Buffer {

private int[] buffer;

private int count; // Number of items in the buffer

private int in = 0; // Index for the producer to put an item

private int out = 0; // Index for the consumer to take an item

private final int size;

public Buffer(int size) {

this.size = size;

buffer = new int[size];

this.count = 0;

}

// Called by the Producer

public synchronized void put(int item) throws InterruptedException {

// Wait if the buffer is full

while (count == size) {

System.out.println("Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases the lock and waits

}

buffer[in] = item;

in = (in + 1) % size;

count++;

System.out.println("Producer: Produced " + item + ". Buffer count: " + count);

// Notify a waiting consumer that a new item is available

notify(); // Wake up one consumer

}

// Called by the Consumer

public synchronized int get() throws InterruptedException {

// Wait if the buffer is empty

while (count == 0) {

System.out.println("Consumer: Buffer is empty. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases the lock and waits

}

int item = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % size;

count--;

System.out.println("Consumer: Consumed " + item + ". Buffer count: " + count);

// Notify a waiting producer that there is space

notify(); // Wake up one producer

return item;

}

}

Why while loop and not if?

This is a critical point called the "spurious wakeup" problem. A thread can sometimes wake up from wait() even if no notify() was called for it. This is a rare, platform-specific behavior. By using a while loop, we re-check the condition (count == size or count == 0) after waking up. If the condition is still true, the thread will simply call wait() again. This makes the code robust.

The Producer Thread

public class Producer implements Runnable {

private Buffer buffer;

public Producer(Buffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

try {

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

buffer.put(i);

Thread.sleep(100); // Simulate time taken to produce

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

The Consumer Thread

public class Consumer implements Runnable {

private Buffer buffer;

public Consumer(Buffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

try {

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

buffer.get();

Thread.sleep(200); // Simulate time taken to consume

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

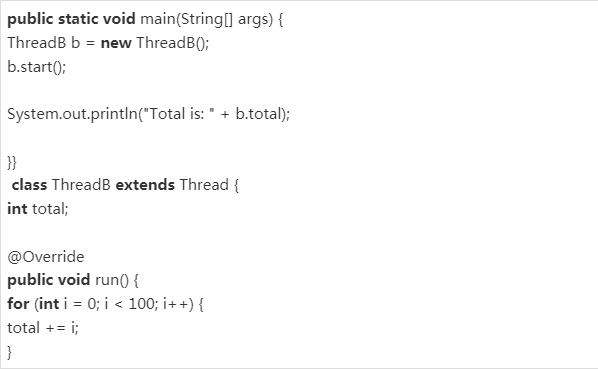

The Main Class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Buffer buffer = new Buffer(3); // A small buffer to easily see waiting

Thread producerThread = new Thread(new Producer(buffer));

Thread consumerThread = new Thread(new Consumer(buffer));

producerThread.start();

consumerThread.start();

try {

producerThread.join();

consumerThread.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Main: Finished.");

}

}

Sample Output

You'll see an output like this, demonstrating the waiting and notification:

Producer: Produced 1. Buffer count: 1

Consumer: Consumed 1. Buffer count: 0

Producer: Produced 2. Buffer count: 1

Producer: Produced 3. Buffer count: 2

Producer: Produced 4. Buffer count: 3

Producer: Produced 5. Buffer count: 3

Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...

Consumer: Consumed 2. Buffer count: 2

Producer: Produced 5. Buffer count: 3

Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...

Consumer: Consumed 3. Buffer count: 2

Producer: Produced 6. Buffer count: 3

Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...

... and so onModern Alternatives (The java.util.concurrent Package)

While wait() and notify() are foundational, they are error-prone. The modern Java concurrency library provides safer and higher-level abstractions.

-

BlockingQueue: This is the recommended solution for the Producer-Consumer problem. It's a thread-safe queue that handles all the waiting and notifying for you.// Example using ArrayBlockingQueue import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue; import java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue; public class ModernProducerConsumer { public static void main(String[] args) { // The queue has a capacity of 10 BlockingQueue<Integer> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(10); Thread producer = new Thread(() -> { try { for (int i = 1; i <= 50; i++) { queue.put(i); // Blocks if the queue is full System.out.println("Produced " + i); } } catch (InterruptedException e) { Thread.currentThread().interrupt(); } }); Thread consumer = new Thread(() -> { try { while (true) { Integer item = queue.take(); // Blocks if the queue is empty System.out.println("Consumed " + item); } } catch (InterruptedException e) { Thread.currentThread().interrupt(); } }); producer.start(); consumer.start(); } } -

java.util.concurrent.locks: This package provides more advanced locking mechanisms likeReentrantLockandConditionobjects.Conditionobjects are essentially more powerful and flexible versions ofwait/notify.

Summary

| Feature | wait() / notify() |

BlockingQueue / Locks |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Low-level, error-prone. | High-level, safer. |

| Control | Fine-grained control over threads. | Abstracts away thread management. |

| Use Case | Learning concurrency fundamentals, very specific custom scenarios. | Most common concurrent tasks (Producer-Consumer, task pools, etc.). |

| Recommendation | Understand them deeply, but prefer java.util.concurrent in production code. |

The standard and recommended approach for new code. |