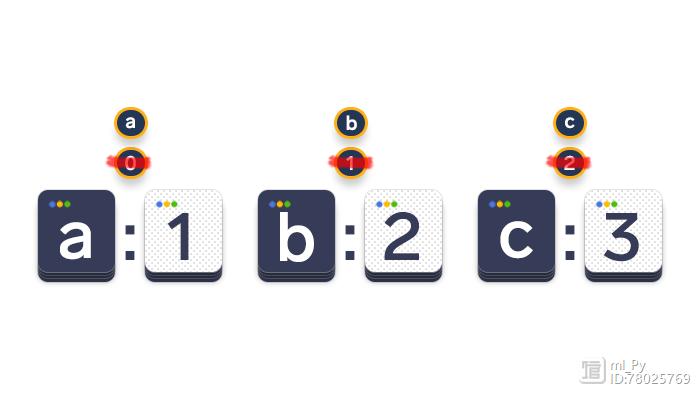

Of course! The enumerate function in Python 2 works similarly to its modern Python 3 counterpart, but with one critical difference in its return type. Understanding this difference is key to writing code that works correctly and avoids common bugs.

The Core Idea of enumerate

enumerate is a built-in Python function that adds a counter to an iterable. It returns an iterator that produces tuples containing a count (starting from 0 by default) and the value from the iterable.

This is extremely useful for when you need both the index and the item itself while looping, without having to manually manage an index variable.

Python 2 enumerate Behavior

In Python 2, enumerate returns a list of tuples.

Basic Syntax

enumerate(iterable, start=0)

iterable: The sequence you want to loop over (e.g., a list, string, tuple).start: The starting number for the counter (defaults to 0).

Example

Let's see it in action. Notice that enumerate immediately generates a list.

# Our data fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] # Using enumerate() in Python 2 # This returns a list of tuples: [(index, value), (index, value), ...] enumerated_fruits = enumerate(fruits) print "Type of enumerated_fruits:", type(enumerated_fruits) # Output in Python 2: Type of enumerated_fruits: <type 'enumerate'> # To see the actual content, we can convert it to a list print "List of tuples:", list(enumerated_fruits) # Output: List of tuples: [(0, 'apple'), (1, 'banana'), (2, 'cherry')]

Common Usage in a for Loop

This is the most frequent use case. Python 2's for loop is smart enough to "unpack" the tuples returned by enumerate automatically.

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

print "Looping with enumerate in Python 2:"

for index, value in enumerate(fruits):

print "Index: %d, Value: %s" % (index, value)

# Output:

# Looping with enumerate in Python 2:

# Index: 0, Value: apple

# Index: 1, Value: banana

# Index: 2, Value: cherry

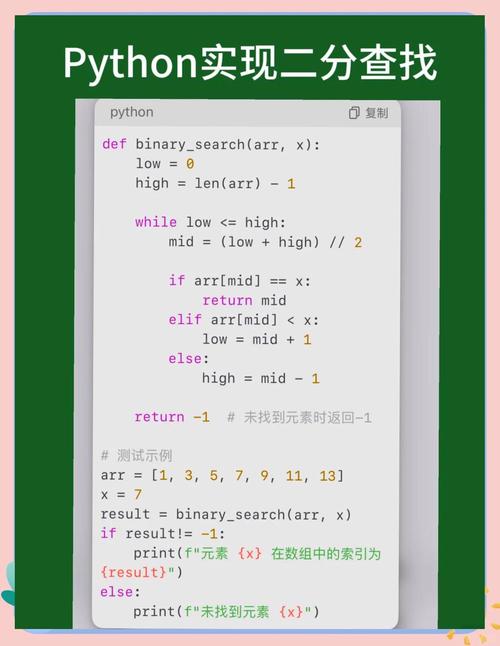

The Critical Difference: Python 2 vs. Python 3

This is the most important part to remember.

| Feature | Python 2 | Python 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Return Type | An iterator object (<type 'enumerate'>) |

An iterator object (<class 'enumerate'>) |

| Evaluation | Behaves like a list for most practical purposes. | Behaves like a true iterator. |

| Key Implication | You can "consume" the object multiple times (e.g., convert it to a list, then loop over it). | You can only iterate over it once. After that, it's exhausted. |

Let's demonstrate this with a code example that will behave differently in the two versions.

# This code will work in Python 2 but fail in Python 3

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

enumerated_fruits = enumerate(fruits)

# --- First Use: Convert to a list ---

# In Python 2, this works. The iterator is not exhausted.

print "First use - converting to a list:"

first_list = list(enumerated_fruits)

print first_list

# Output in Python 2: [(0, 'apple'), (1, 'banana'), (2, 'cherry')]

# --- Second Use: Loop over it ---

# In Python 2, this ALSO works because the iterator state was not

# fully consumed by the list() call in the same way it is in Python 3.

print "\nSecond use - looping:"

for index, value in enumerated_fruits:

print "Index: %d, Value: %s" % (index, value)

# Output in Python 2: (This loop will run successfully)

# Index: 0, Value: apple

# Index: 1, Value: banana

# Index: 2, Value: cherry

Why the difference?

- In Python 2,

enumeratereturns a list-like object. When you pass it tolist(), it generates the full list. The object itself still has its internal pointer, so you can iterate again. - In Python 3,

enumerateis a true iterator. When you pass it tolist(), the iterator is run to completion to build the list. After that, the iterator is exhausted and has no more items to give. If you tried to loop overenumerated_fruitsagain in Python 3, the loop would not run.

Practical Example: Modifying a List While Iterating

A common pattern is to modify a list based on its index. enumerate is perfect for this.

Goal: Remove all fruits with an odd index.

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry', 'date', 'elderberry']

print "Original list:", fruits

# Output: Original list: ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry', 'date', 'elderberry']

# We iterate using enumerate to get the index

for index, fruit in enumerate(fruits):

# If the index is odd (1, 3, 5, ...)

if index % 2 == 1:

# Remove the item at that index

# Note: We use `index` directly because `enumerate` gives us the current index

del fruits[index]

print "Modified list:", fruits

# Output: Modified list: ['apple', 'cherry', 'elderberry']

This works cleanly in both Python 2 and 3 because the loop is consuming the iterator as it goes.

The Python 2 xrange and enumerate Combination

When working with large sequences in Python 2, you should always prefer xrange over range to save memory. xrange creates a sequence that generates numbers on demand, just like Python 3's range.

You can combine enumerate with xrange for memory-efficient looping.

# Bad for large numbers (creates a full list in memory)

# for i in range(1000000): ...

# Good for large numbers (uses an iterator)

# for i in xrange(1000000): ...

# Combining with enumerate is also very efficient

print "Using enumerate with xrange:"

for index, number in enumerate(xrange(5)): # xrange(5) generates 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

print number

# Output:

# 0

# 1

# 2

# 3

# 4

Summary and Key Takeaways for Python 2

- What it is:

enumerateadds a counter to an iterable, returning an iterator that yields(index, value)tuples. - How to use it: The standard

for index, value in enumerate(my_list):is the most common and Pythonic way. - Return Type: It returns an

enumerateobject, which behaves like a list for most purposes, allowing you to iterate over it multiple times (unlike Python 3). - Python 2 vs. 3: Be aware of this key difference if you are writing code that needs to be compatible with both versions or if you are porting code from Python 3 to Python 2. In Python 2, you can "re-use" an

enumerateobject, but in Python 3, you cannot. - Use

xrange: For large loops, pairenumeratewithxrangefor better memory efficiency.