Of course! This is a fundamental topic in Python, especially for developers who have worked with both Python 2 and Python 3. Let's break it down.

The Short Answer (TL;DR)

- In Python 3:

stris the native string type, and it is fundamentally Unicode. Thestr()function creates a Unicode string. The oldunicodetype from Python 2 has been completely removed. - In Python 2:

strwas a sequence of bytes, whileunicodewas a sequence of Unicode code points.str()created a byte string, andunicode()created a Unicode string.

The rest of this answer will explain the "why" and the details behind this distinction.

The Core Problem: Bytes vs. Characters

To understand str and unicode, you must first understand the difference between bytes and characters.

- Bytes: A byte is a unit of digital information that consists of 8 bits. It's just a number from 0 to 255. It has no inherent meaning on its own. It could represent part of an image, a piece of an executable program, or a character.

- Characters: A character is an abstract symbol, like the letter 'A', the euro sign '€', or a Chinese character '字'. How a computer stores this character is the key.

Historically, different systems used different mappings of bytes to characters. This led to chaos. For example, the byte 0xE9 could mean 'é' on one system and something completely different on another.

The Solution: Unicode

Unicode is a universal character set. It aims to assign a unique number (called a code point) to every character in every language in the world. This code point is typically written as U+xxxx (e.g., U+00E9 for 'é', U+4E2D for '中').

Unicode itself is just a giant lookup table. It doesn't specify how to store these code points in memory. That's the job of an encoding.

An encoding is a set of rules for converting between Unicode code points and a sequence of bytes.

- UTF-8: The most common encoding. It's a variable-width encoding. It uses 1 byte for ASCII characters (which is why it's so space-efficient for English text) and up to 4 bytes for other characters.

- UTF-16: Uses 2 or 4 bytes per character. Common in Windows and Java environments.

- ASCII: A 7-bit encoding that can only represent 128 English characters. It's a strict subset of UTF-8.

Python 2: The Two-String World

This is where str and unicode were both necessary.

str in Python 2

A str object was a sequence of bytes. It had no idea what those bytes meant. It was just a bag of data.

# Python 2 s = "hello" print type(s) # <type 'str'> print len(s) # 5 (5 bytes) print repr(s) # 'hello' (looks like characters, but it's bytes) # If you try to put non-ASCII characters in a str, Python 2 gets confused # unless you declare the source file encoding. # s = "héllo" # This would raise a SyntaxError in a default .py file

unicode in Python 2

A unicode object was a sequence of Unicode code points. It understood characters.

# Python 2

u = u"héllo"

print type(u) # <type 'unicode'>

print len(u) # 5 (5 characters)

print repr(u) # u'h\xe9llo' (The \xe9 is the *byte* representation, but the object itself holds the character 'é')

# You can create a unicode object from a str by decoding it

s = "h\xc3\xa9llo" # This is the UTF-8 byte representation of "héllo"

u = s.decode('utf-8')

print u # héllo

The Bridge: encode() and decode()

To move between the two worlds, you had to explicitly convert them:

unicode_string.encode(encoding): Turns aunicodestring into astr(bytes) using a specific encoding.str_string.decode(encoding): Turns astr(bytes) into aunicodestring, assuming it was encoded with a specific encoding.

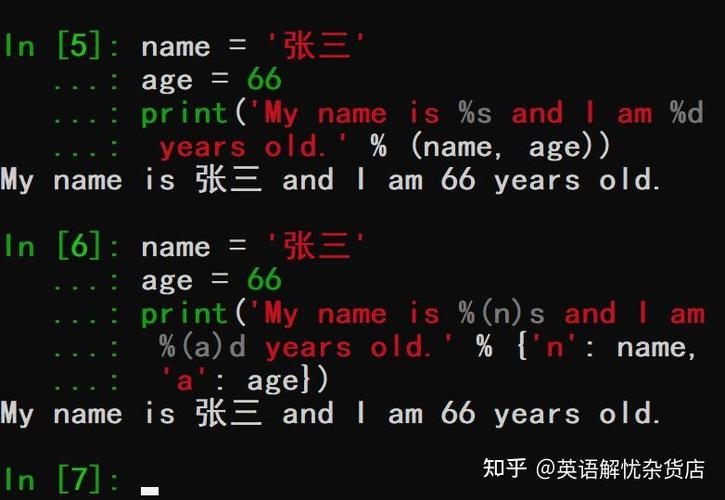

Example in Python 2:

# A string of bytes, encoded in UTF-8

utf8_bytes = "Caf\xc3\xa9" # Represents "Café"

# To work with it as characters, you must DECODE it

unicode_string = utf8_bytes.decode('utf-8')

print unicode_string # u'Caf\xe9' (internally, it knows this is the character 'é')

print type(unicode_string) # <type 'unicode'>

# To save it to a file or send it over a network, you must ENCODE it

back_to_bytes = unicode_string.encode('utf-8')

print back_to_bytes # 'Caf\xc3\xa9'

print type(back_to_bytes) # <type 'str'>

Python 3: The One-String World (The Modern Way)

Python 3 was designed to solve the ambiguities of Python 2. The philosophy is: "Text is text, and bytes are bytes. Never the twain shall meet."

str in Python 3

This is the new, improved string. It is natively a sequence of Unicode characters. It is what unicode was in Python 2.

# Python 3 s = "hello" print(type(s)) # <type 'str'> print(len(s)) # 5 (5 characters) # Non-ASCII characters work perfectly fine in a source file (if saved as UTF-8) s = "héllo" print(type(s)) # <type 'str'> print(len(s)) # 5 (5 characters) print(repr(s)) # 'héllo'

bytes in Python 3

The old str type from Python 2 was renamed to bytes in Python 3. It is, just like before, a sequence of bytes. It's used for raw data like network packets, file contents, or images.

# Python 3 # To create a bytes object, use a 'b' prefix b = b"hello" print(type(b)) # <type 'bytes'> print(len(b)) # 5 (5 bytes) print(repr(b)) # "b'hello'" # Non-ASCII bytes in a bytes object are shown as their integer values b = b"h\xc3\xa9llo" # The UTF-8 bytes for "héllo" print(repr(b)) # "b'h\\xc3\\xa9llo'"

The Bridge in Python 3: encode() and decode()

The concept is the same, but the types are cleaner.

str.encode(encoding): Turns astr(text) intobytes.bytes.decode(encoding): Turnsbytesinto astr(text).

Example in Python 3:

# A bytes object, encoded in UTF-8

utf8_bytes = b"Caf\xc3\xa9" # Represents "Café" as bytes

# To work with it as text, you must DECODE it

text_string = utf8_bytes.decode('utf-8')

print(text_string) # 'Café'

print(type(text_string)) # <class 'str'>

# To save it to a file or send it over a network, you must ENCODE it

back_to_bytes = text_string.encode('utf-8')

print(back_to_bytes) # b'Caf\xc3\xa9'

print(type(back_to_bytes)) # <class 'bytes'>

Summary Table

| Feature | Python 2 | Python 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Native Text String | unicode |

str |

| Native Byte String | str |

bytes |

What str() does |

Creates a str (byte string). |

Creates a str (Unicode string). |

What unicode() does |

Creates a unicode (text) string. |

Removed. Use str() instead. |

| Core Idea | You have two types, str and unicode, and you must constantly convert between them using .encode() and .decode(). |

You have two distinct types: str for text and bytes for binary data. Python 3 code is much cleaner because it doesn't accidentally mix them. |

| Best Practice | Always work with unicode objects in your application logic and only encode to str at the very last moment (e.g., when writing to a file or sending a network request). |

Always work with ` |